Acid Reflux, Morbid Obesity and How Bariatric Surgery Affects GERD

Acid reflux occurs when stomach contents leak out into the tube connecting the mouth to the stomach. Common symptoms include heartburn, an unpleasant taste in the mouth and difficulty swallowing. Less commonly, throat pain, nausea, coughing and increased salivation may also be observed, and frequent reflux is associated with an increased risk of tooth decay due to acid erosion.

Obesity changes intrabdominal pressures

Most people will experience occasional episodes of symptomatic acid reflux, and it is usually no cause for concern. When reflux occurs more frequently it is classed as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and if left untreated can lead to serious complications.

What is the Pathophysiology of Reflux Disease

The stomach is connected to the throat or pharynx by the esophagus; a long tube that enters the abdominal cavity via an opening in the diaphragm known as the hiatus. Each end of the esophagus is surrounded by a ring of muscle called a sphincter, which is normally contracted but which relaxes upon swallowing to allow passage of food into the stomach. The main function of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) is to prevent food from entering the windpipe, actively directing it into the esophagus during swallowing. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is surrounded by a sling of diaphragmatic muscle fibers known as the crural diaphragm, which works in tandem with the LES to form a one-way valve that prevents stomach acid, duodenal bile and partially digested food from flowing up into the esophagus. The esophagus joins the stomach at an acute angle, known as the angle of His, which further serves to protect the esophagus from reflux of acidic stomach contents.

In addition to brief periods of relaxation triggered by swallowing, the LES also opens spontaneously for prolonged periods of up to a minute, in order to allow gas to pass from the stomach as a belch. This action is known as transient lower esophageal relaxation (TLESR), and is thought to be triggered by build-up of gas within the stomach, or gastric distention, which frequently occurs after a meal or ingestion of carbonated drinks. It is quite common for reflux to occur during episodes of TLESR, which are known to increase in frequency during sleep and when lying down.

In simple terms, GERD occurs due to incomplete LES closure or when TLESR occurs more frequently than normal, but the precise mechanisms underlying GERD are not fully understood. Known risk factors for GERD include smoking, pregnancy, a high-fat diet and obesity. Genetic factors are also thought to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of GERD, with a first-degree family history strongly linked to increased susceptibility, independent of obesity.

How are Reflux Disease and Obesity Related?

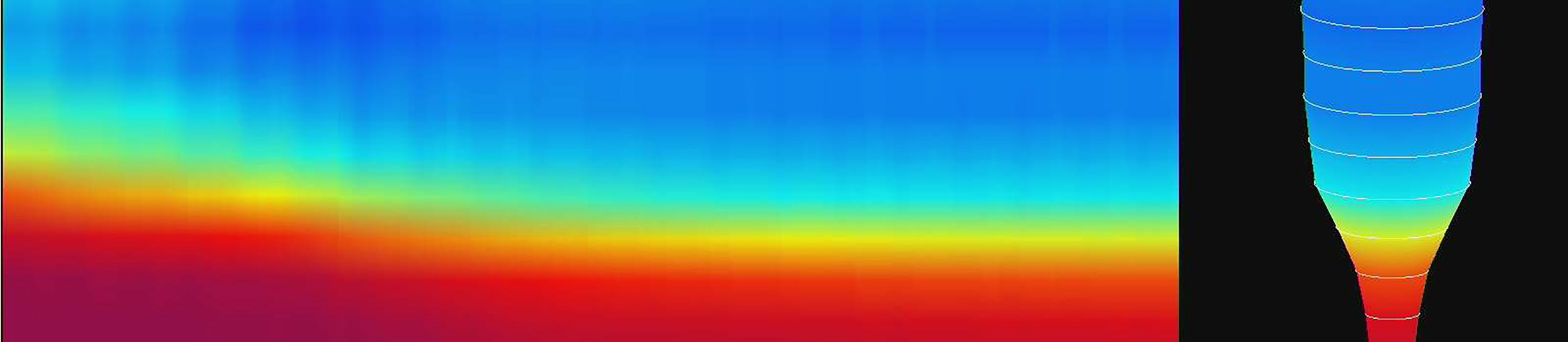

The dose-response relationship between obesity and GERD is well-known: increased body mass index (BMI) closely correlates with an increase in prevalence of GERD. However, recent studies have suggested that waist circumference may be a more significant predictor of risk than BMI. Central obesity, as indicated by a high waist-to-hip ratio, is known to increase pressure within the stomach. This lends support to the theory that GERD occurs as a result of such raised intragastric pressure, under which condition the LES may be forced open. Some authors have also suggested that obesity may somehow alter the sensitivity of the esophagus, such that episodes of reflux are more likely to induce discomfort and therefore be reported more frequently by obese individuals relative to the general population.

Several obesity-related conditions, including diabetes and hiatus hernia, carry particular risk for developing GERD. Impaired gastric emptying, or gastroparesis, is a common complication of diabetes. The persistently high levels of blood sugar characteristic of diabetes can affect the nerves of the stomach, resulting in delayed processing of stomach contents. Gastroparesis can lead to an increase in stomach contents volume and acid secretion, both of which may contribute to the link between gastroparesis and GERD.

Diaphragmatic Hernia seen during gastric bypass

Hiatus hernia is a condition in which the LES separates from the crural diaphragm, such that the LES and upper part of the stomach can protrude through the hiatus into the chest cavity. Hiatus hernias are frequently asymptomatic, but when symptoms do present, they are frequently those of GERD. What underlies this link between hiatus hernia and reflux has yet to be established. However, a relationship is known to exist between the size of a hiatus hernia and LES pressure, with larger hernias resulting in decreased LES pressure. Additionally, the presence of a hiatus hernia is known to result in more frequent episodes of TLESR. It has also been suggested that GERD itself could be a cause of hiatus hernia in some cases, with scarring from frequent acid exposure causing the esophagus to shorten, pulling the stomach upwards through the hiatus. Obesity is a major risk factor for hiatus hernia, and a specific correlation between waist circumference and separation of the LES and crural diaphragm is known to exist.

Complications of Chronic Reflux Disease

Frequent exposure to acidic stomach contents can damage the lining, or mucosa, of the esophagus, causing it to become irritated or inflamed, sometimes resulting in formation of ulcers which may bleed. This condition, known as esophagitis, can lead to extreme discomfort, scarring and difficult painful swallowing.

In some individuals, chronic acid exposure can cause the esophageal mucosa proximal to the LES to undergo a process known as metaplasia, in which the normal squamous lining cells are converted to columnar cells of a type similar to those found in the stomach or small intestine. This condition, called Barrett’s esophagus, is typically asymptomatic, but is of significance due to its association with increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma; a rare form of cancer with a low survival rate.

Obese patients tend to have more severe esophagitis and obesity has been identified as an independent risk factor for development of Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma.

How do Bariatric Procedures Improve Reflux?

Research suggests significant correlation between weight loss and symptomatic reduction in GERD, with results from a recent study indicating that weight loss through lifestyle changes alone, or in conjunction with bariatric surgery, can lead to complete resolution of GERD symptoms. Additionally, because bariatric procedures involve modification of the digestive tract, they can also directly influence GERD symptoms, with probable outcomes differing, dependent on the specific procedure.

Gastric Bypass (RYGB) is an Optimal Treatment for Reflux

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is well-established as a highly effective treatment option for GERD in the obese and morbidly obese, and is therefore the most commonly selected bariatric procedure when GERD is a factor. More recently, several studies have indicated RYGB to be a viable treatment option for GERD in non-severely obese patients.

The procedure involves creating a small gastric pouch from the upper part of the stomach, then bypassing the rest of the stomach and part of the digestive tract by removing a section of small intestine before reconnecting the pouch to the remainder. Food intake is limited by the pouch, and absorption of nutrients and calories reduced by the shortened intestinal pathway, dually facilitating weight loss. Postoperative reduction in circulating levels of the hunger-stimulating hormone ghrelin has also been proposed as a third mechanism for weight loss following RYGB surgery.

The RYGB procedure is thought to impact upon GERD by reducing overall stomach acid production and stomach contents volume. Other physiological effects of the new anatomic configuration may also be implicated.

Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG) and Potential Long-term Problems with Reflux

Sleeve gastrectomy was originally described as the first part of a multi-stage duodenal switch or gastric bypass operation, designed to promote initial weight loss in morbidly obese individuals for whom undergoing the entire procedure in a single stage would present too high a risk. However, for many individuals, weight loss was found to be sufficient following the sleeve procedure alone, removing the need for a second operation.

Normally performed laparoscopically, SG involves vertical division of the stomach such that the original route of food through the digestive tract is preserved, but most of the stomach is removed to leave a long curved pouch. The technique requires direct modification of the gastro-esophageal junction, straightening the angle of His and partially sectioning the sling formed by the crural diaphragm, hence the presence of Barrett’s esophagus is considered to be a contraindication.

Studies of the long-term effects of SG upon GERD suggest a typical pattern that involves worsening of symptoms during the immediate postoperative period, followed by a reduction in symptoms as significant weight loss occurs. In the longer term, many patients report symptomatic reoccurrence of GERD within two to three years postoperatively. The reasons for this are not well understood but the anatomic modifications to the gastro-esophageal junction, reduced churning capabilities of the small gastric pouch, and elevated pressure within the pouch have been implicated. The net result is that SG is considered to be the least effective bariatric procedure for controlling GERD. Weight loss following SG is also thought to be less than is achievable with RYGB. However, the technique does offer some advantages over other bariatric procedures in that it is less malabsorbtive than RYGB, and avoids the potential complications associated with placement of a foreign object within the body, as occurs with the Lap-Band procedure.

The Lap-Band and Reflux

The Lap-Band is an adjustable system designed to facilitate reduced food intake via the creation of a small gastric pouch. It differs from the other procedures in that the stomach is left intact. During surgery, an adjustable silicone ring is placed around the top of the stomach beneath the gastro-esophageal junction, creating a small pouch above the ring whilst leaving the rest of the stomach intact underneath. A thin length of silicone tubing extends from the ring to an externally sited port, through which saline solution can be injected. The inner surface of the ring comprises a number of inflatable chambers that can be used to control the diameter of the opening dependent upon how much saline is introduced. This method allows the ring to be adjusted by the surgeon post-operatively in an outpatient setting. Of the three methods discussed, Lap-Band surgery generally results in the lowest weight losses, but is a non-malabsorbtive and reversible procedure.

A recent study investigating the impact of Lap-Band surgery upon GERD reported symptomatic reduction in the majority of individuals undergoing surgery, independent of postoperative weight loss, suggesting that the Lap-Band is a viable treatment option for GERD in the obese and morbidly obese. It is thought that the silicone ring facilitates symptomatic reversal of GERD by acting as an additional two-way valve to augment LES function.