The spleen and its role in immune function

The spleen is a brownish fist-sized organ located in the upper left side of the abdomen, tucked into a space between the stomach, pancreas and left kidney. It’s one of those organs that people know about, but aren’t sure what it does. Essentially, the spleen is a storage container and filter for blood, though it is part of the lymphatic system. In fact, it’s the largest lymph node in the body. One of its tasks is to remove harmful bacteria and viruses in the blood stream. Its other major task is removing or storing certain blood cells.

The Spleen Filters and Attacks

The spleen is not part of the digestive system however is connected to the blood vessels of both the stomach and the pancreas. The spleen is situated on the left side of our body; under the ribs and above the stomach. It is a part of the lymphatic system and can weigh between 150 – 200 grams in a healthy adult and is approximately 10-12 cm in its longest dimension.

The spleen reacts to disease

As you might expect from an organ that filters the blood, the spleen is responsive to any injury or disease that affects the blood supply. When something goes wrong with the spleen, it’s usually a reaction to something elsewhere in the body. The list of diseases that may have serious impact on the spleen is long, to name a few: Malaria, sickle cell anemia, leukemia, pernicious anemia, Hodgkin’s disease, mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus, and sarcoidosis.

The spleen and its unknown roles

These diseases cause the spleen to become very active. When it does, it processes and stores more blood, which frequently causes it to enlarge. This is normal and usually disappears when the disease goes away. However, sometimes chronic enlargement develops, a condition called splenomegaly (splen-o-MEG-allee). This may indicate the spleen is too active in removing red blood cells or platelets, making the disease conditions worse. Occasionally, the spleen becomes so large – massive splenomegaly – it pushes on nearby organs and blood vessels. This may be a reason to remove the spleen.

Two types of spleen tissue: red pulp and white pulp

The spleen is composed of two primary regions namely, red pulp and white pulp. The red pulp makes up for little more than three-fourth of the spleen. A region designated marginal zone is a transition area that separates it from the white pulp.

Red pulp

Red pulp is red because it has many small cavities (sinusoids) where the spleen stores blood in case of injury or other situations where the body needs extra blood. This blood reserve has a high count of platelets, an essential component for blood coagulation to help stop bleeding. Red pulp also removes and recycles components of old, damaged and dead red blood cells.

White pulp

White pulp is associated with the lymphatic function of the spleen. Most of this tissue consists of lymph-related nodules, called Malphighian corpuscles. The white pulp works as part of the immune system, producing antibodies (immunoglobin) that recognize and neutralize harmful antigens (bacteria and viruses) in the blood. It also produces and stores white blood cells (lymphocytes).

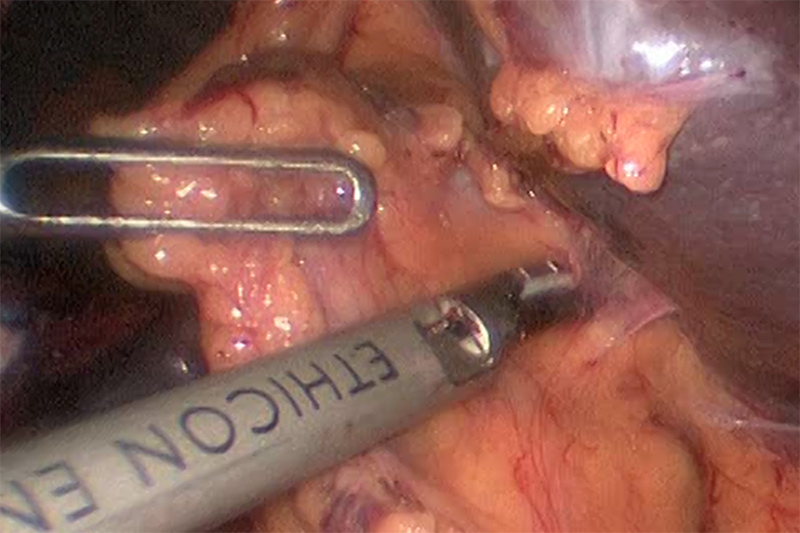

Splenectomy – removal of the spleen

In addition to splenomegaly, other conditions that may require removal of the spleen include cancer of the spleen (usually lymphoma), ruptured spleen (from an accident or blow) and loss of blood supply to the spleen (infarct with spleen necrosis). While removal of the spleen – a splenectomy – is a major operation, the spleen is not a vital organ and the body tolerates its removal. This is especially true with laparoscopic splenectomy, where the spleen is removed through a few small ‘ports’ (holes) in the abdomen rather than large open incisions.

Laparoscopy used to dissect tissue around the spleen

Because of its role in filtering the blood and as part of the immune system, people without a spleen need to be alert for conditions such as infections and inflammation, as the body is less able to resist certain bacteria and some vaccines are less effective.