Why is pancreatectomy needed?

For most people the pancreas is one of those organs little understood or even noticed, until something goes wrong. It’s a relatively small organ, about the size and shape of a hot-dog bun, nested in a curve of the upper intestine and surrounded by the stomach, spleen, kidneys and intestines. The pancreas has three anatomical regions: the head, which is the portion closest to the upper intestine and contains the main pancreatic duct into the duodenum, the body or middle section of the pancreas, and the tail portion adjacent to the spleen.

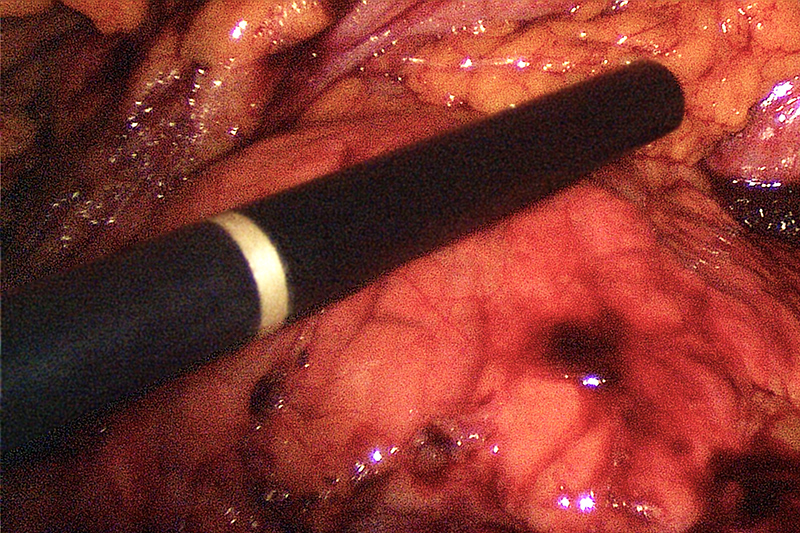

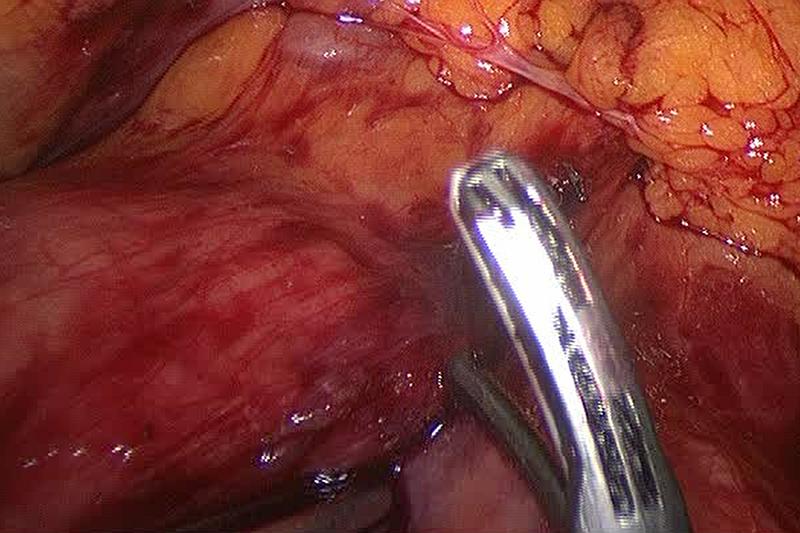

Minimally Invasive Pancreatectomy being Aided by Ultrasound

Along with the liver and glands in the small intestine, the pancreas produces and regulates the chemistry of the digestive system. For the pancreas, this means two principle functions. One is the role it plays in regulating the amount of sugar in the blood, which is part of the endocrine (hormone) system. The other role, part of the exocrine (digestive) system, is producing many of the enzymes that convert what we eat and drink into useful nutrients – sugars, vitamins, minerals – that are absorbed into the blood stream through the walls of the intestines.

Within the pancreas, the two functions, endocrine and exocrine, have their own tissues. About a million islets of Langerhans produce the endocrine hormones, which enter the blood stream through a dense network of tiny blood vessels (capillaries). Acinar cells produce many of the enzymes of the exocrine system, which flow to the duodenum through a network of ducts. The tissues of these two systems exists side-by-side but unconnected, which can complicate surgery.

We eat and drink primarily to acquire energy and water, secondarily to maintain levels of vitamins, minerals, proteins and other nutrients. In the broad picture, the pancreas is a key part of a very complicated feedback system that monitors the levels of blood sugar (energy source) and the composition of what we eat to regulate hunger, thirst, and the process of digestion. It’s a relatively robust system that most of the time manages to keep us alive and healthy, but it’s not invulnerable.

Long-term lifestyle patterns affect the pancreas and all the organs of the digestive system. Among other things, continual overeating, eating too much of certain foods (fats, sugars), smoking and consumption of alcohol strain the system. In a variety of ways, the pancreas sometimes reacts to the strain by developing serious medical conditions.

Diseases of the pancreas that may require pancreatectomy

It’s fair to say that when the pancreas develops a condition, it’s often serious and potentially life threatening. The seriousness frequently becomes worse because many diseases of the pancreas go undetected until they are well advanced. At this stage, the inflammation and pressure may announce itself by intense pain.

Pancreatitis is an inflammation of the pancreas with two forms, acute, which is usually the results of gallstones blocking the pancreatic duct (about 60% of cases), and chronic, which is usually caused by alcoholism. Acute pancreatitis often causes extreme pain, frequently associated with eating, and requires hospitalization. Depending on the location of the inflammation, and the cause, surgery to remove a segment of pancreas tissue – a partial pancreatectomy – may be treatment for some cases of acute pancreatitis.

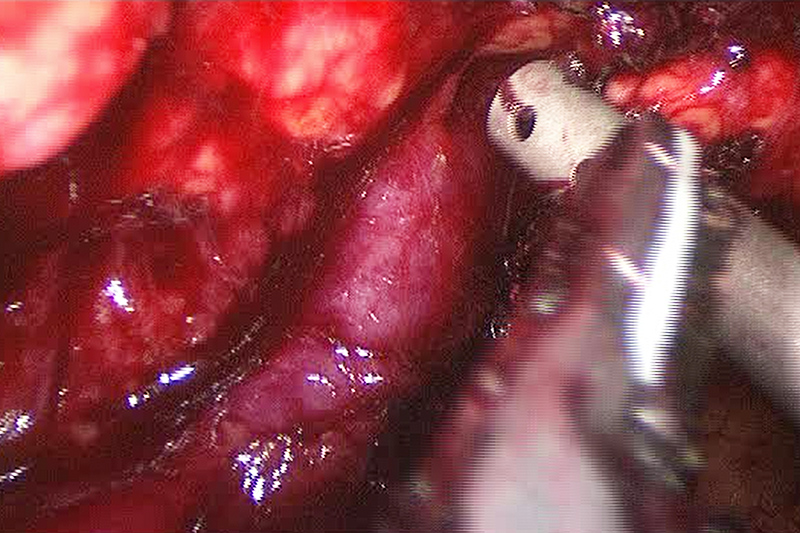

Surrounding Tissue Dissected off the Pancreas

Diabetes Mellitus in two types (type 1 and 2) is a metabolic disease where there is too much sugar in the blood, either because the pancreas is not producing enough insulin (type 1) or where the cells of the body no longer respond to insulin (type 2). This is by far the most common disease of the pancreas, affecting more than 300 million people worldwide. Drug therapy and insulin replacement are the usual forms of treatment. Surgery is rarely involved unless a cyst, tumor or tissue damage is responsible for the loss of insulin production.

Benign pancreatic tumors and cysts are relatively common, especially as people grow older. When the cysts become large or have a high probability of becoming cancerous, surgical removal by partial pancreatectomy may be an appropriate treatment.

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States and is the most common reason for pancreatectomy. About 95% of pancreatic cancer tumors are a type of adenocarcinoma, glandular-style tumors found in the ducts and acinar cells of the exocrine system. In a small percentage of cases, the endocrine system may develop neuroendocrine tumors.

The diagnostic process leading to a pancreatectomy

Diagnosis of a condition suggesting a pancreatectomy can be complicated. It starts with the patient condition, which usually involves considerable pain, weight loss or jaundice (yellow colored skin). These are also symptoms of other diseases, which is typical of most pancreas conditions, making them difficult to diagnose in the early stages. A major consideration will be the overall health of the patient, including risk factors such as obesity, tobacco smoking, alcoholism, diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, family history, age and lifestyle (especially diet).

In a physical examination, the doctor will try to isolate the source of pain, for example as sensitivity in the abdomen. If the physician suspects a pancreatic condition, the usual follow-up includes blood work (testing) and scanning, such as ultrasound, X-ray computed tomography (CT), abdominal MRI, or a cholangiogram. The scanning will reveal the location of lesions, cysts and tumors, which can relate to the original symptoms. For example, with cysts or tumors in the head of the pancreas, where there may be pressure on or blockage of the pancreatic duct, weight loss, improper fat digestion and jaundice are frequent symptoms.

Removing even a small part of the pancreas is a delicate operation with considerable trauma. This makes the decision to perform a pancreatectomy conditional on the characteristics of the disease, for example, if the diagnosis is adenocarcinoma, which tends to lodge itself among the ductwork of the pancreas, surgical procedures are difficult and have a lower chance of success. On the other hand, well-formed cysts or tumors, especially in the tail or body of the pancreas are often a successful target.

Treatment for pancreatic conditions

Treatment for conditions such as pancreatitis and diabetes usually consists of a combination of diet and drugs or insulin replacement. In rare circumstances, such as injury or the effect of a tumor, is surgery involved. Physical injury, such as from an accident, and some cases of internal bleeding in the pancreas (hemosuccus pancreaticus) may require pancreatectomy. Otherwise, the most frequent conditions for pancreatectomy, especially a distal (middle or tail section) pancreatectomy are cysts and pancreatic cancer.

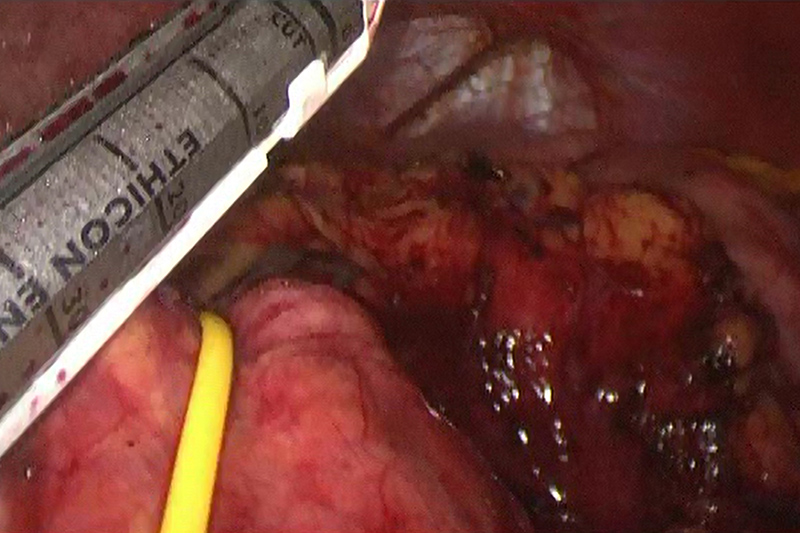

Different maneuvers for laparoscopic dissection

Assessment of risk for a pancreatectomy

Any surgery on a major organ carries risk. Historical records show a 50% morbidity (severe complications) and 5% mortality. These odds have improved over the last decade, but the pancreas is one of the more difficult organs for surgery. For one thing, it nests in an area crowded with other organs and blood vessels, particularly the spleen and splenic artery. For another, the physical interweaving of exocrine and endocrine tissue almost invites collateral damage when operating on one or the other system.

Traditionally, pancreatic surgery uses the open method, where large incisions allow the surgeon to pull back skin and tissue to reveal the pancreas. This approach has the advantage of relatively clear view and ease of handling the organs. However, the large incisions expose the abdominal cavity to the air for a considerable time, increasing the risk of infection. It also involves considerable tissue trauma resulting in more pain, longer hospital stays and a longer recovery period.

As an alternative to open surgery, laparoscopic surgery accesses the pancreas through three or four incisions of only a few centimeters in length. While the surgeon must rely on a camera view of the pancreas, a skilled surgical team can perform a laparoscopic pancreatectomy in shorter time, with less blood loss, lower morbidity, shorter hospital stays, and fewer fatalities than open surgery. In short, it can lower the risk for some kinds of pancreatectomy.

Deciding when to use laparoscopic pancreatectomy

The most common and generally successful laparoscopic treatment for the pancreas is the laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy, or the removal of a portion of the pancreas from the body or tail sections. This procedure is most often performed on benign lesions, neuroendocrine tumors or low-grade malignancies (especially cystic tumors). It is less effective with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. There are a number of other conditions, such as physical damage to the pancreas caused by impact, potentially cancerous lesions (pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms) and pancreatic transplants, where a laparoscopic pancreatectomy may be the best choice.

As mentioned, all operations on the pancreas, open or laparoscopic, are difficult. In particular, operations on the tail and body often involve the spleen and splenic artery. When the portion of the pancreas for removal contains a benign cyst or tumor or when the malignant tumor has not metastasized, it is very desirable to leave the spleen and its blood vessels intact. In other cases, especially where metastasization occurred, it is prudent to remove the spleen with a laparoscopic splenectomy or in this case a double operation - a splenopancreatectomy.

The laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy operation

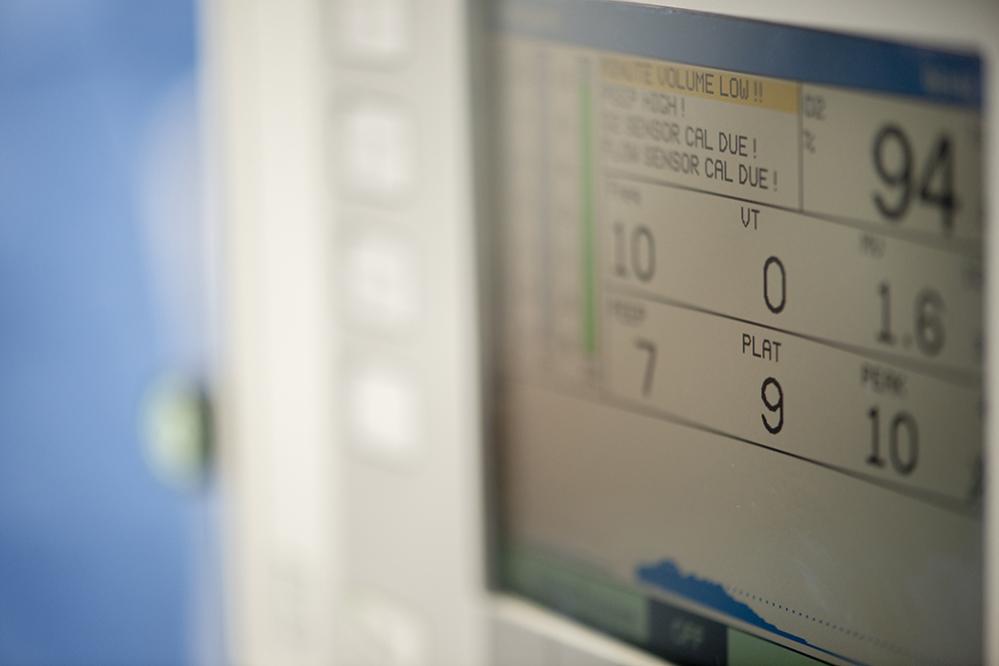

A laparoscopic procedure is a team effort involving a surgeon and one or two assistants, the laparoscopic camera operator, and anesthesiologist. As with most abdominal surgery, general anesthesia is standard for the procedure, as is a tube from the mouth to the airway (an endotracheal tube) attached to a breathing machine (ventilator) and a tube from nose to stomach to prevent nausea and vomiting.

Stapling across the body of the pancreas

In preparation for the laparoscopy, pumping in carbon dioxide gas inflates the abdominal cavity to give the surgeon more room to work. Depending on the surgeon’s preference, three or four incisions (ports created with a surgical instrument called a trocar) provide access to the pancreas for the procedure. One incision, usually the first, is for the laparoscopic camera, which provides the surgical team with a view of the pancreas and the area for surgery (the surgical field) in one or more monitors. The second and third incisions are for access by surgical instruments, and the fourth incision, if there is one, is somewhat larger to allow the surgeon’s hand to guide the operation and remove the portion of the pancreas involved in the pancreatectomy.

Before resecting the pancreas (removing a portion), the decision to leave or remove the spleen must be finalized. The surgical team may start with a plan to conserve (save) the spleen its blood vessels but see during the operation that this is not possible, for example, if the pancreatic cancer has spread to the spleen. The team can also switch at this point to an open surgery if complications make direct manipulation of the organs desirable.

After dealing with the spleen and the blood vessels shared by the pancreas, the surgeon then frees (mobilizes) the area of the pancreas for resection. The resection area is isolated from the rest of the parenchyma (tissue of the pancreas), often by stapling. Then the area is cut away and placed in a laparoscopic removal bag in order to bring it through the largest incision port.

Continued Treatment – Follow up

Following the operation, most patients remain in the hospital from 3-5 days, depending on their general condition and if there are any complications. A short stay in the post-anesthesia care unit, an IV tube for hydration, medicine and nutrition, pain medication, and possibly tubes for the stomach and abdominal incisions are typical for post-operation care.

In addition to risks associated with abdominal laparoscopy, such as infection of port sites, laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy carries other minimal post-operative risks, including:

- Fistula – internal bleeding due to breaks in sutures, tissue tearing or weakened organ wall areas

- Weight loss – of 10-15 lbs. is common with this surgery

- Diabetes – usually temporary but sometimes type 1 induced by the procedure

- Pancreatic enzyme insufficiency – where the pancreas no longer produces enough enzymes for the complete digestion of food. This may require enzymatic replacement.

- Blood loss – a transfusion may be needed if enough blood was lost during the procedure

Once the patient goes home, there is a period of recovery, which may last two to three weeks. A special diet is often necessary along with pain medication, care of the incisions (change of dressing), and limited activity.

Because a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is generally performed on well-defined targets, most often benign tumors or cysts, the success rate is quite good. Roughly, 19%-25% of patients experience post-operative complications, with a reoperation rate of 3%, compared to 12% for open pancreatectomy. The average hospital stay for patients with complications is 11 days, compared to 29 days for the open method.

Although as surgical procedures go, the laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is relatively new, over the past decade, it has proven to be safe and effective with far less trauma and better recovery than open surgery. This procedure is also a candidate for robotic assisted surgery, which brings a high level of surgical accuracy and efficiency, when the surgical team is well prepared.