Paraesophageal

A hernia occurs when an internal body part pushes into an area where it doesn't belong. The hiatus is a normal opening in the muscle that separates the chest cavity from the abdomen which moves up and down with breathing. Although the hiatus is a normal opening, there are occasions when this opening enlarges and the stomach or other organs can slip up inside the chest. This occasion of an abnormally large opening of the hiatus is called a hiatal hernia.

Paraesophageal hernias account for only 5% of all hiatal hernias. A paraesophageal hernia is a type of hiatal hernia where the junction of the stomach and the esophagus remains in place, but part of the stomach is squeezed up into the chest beside the esophagus.

What are the symptoms of a paraesophageal hernia?

A large proportion of patients with a paraesophageal hernia are asymptomatic. This means that they don’t have any symptoms, or that their complaints are so minor that it is hard to associate the complaints with the physiologic problem of the hernia. Symptoms can include a vague discomfort in the top part of the stomach or lower chest known as the epigastric and substernal regions, respectively.

Paraesophageal

Patients can also complain of feeling very full after eating in a manner that is out of proportion to the amount of food that typically caused feelings of fullness. Nausea and problems swallowing (dysphagia) may also occur from gastric volvulus. Pain from a paraesophageal hernia may sometimes be so severe that patients may think that they are suffering from a heart attack.

When a hiatal hernia is large, portions of the intestines other than the stomach may enter the chest cavity. These organs can compress the lung tissue that is meant to occupy the same space resulting in pulmonary complications. Pulmonary problems include recurrent pneumonia or infections. Chronic compression may cause a condition where the lung doesn’t expand properly known as atelectasis. If the hernia is large than difficulty breathing or dyspnea may sometimes occur.

If I have GERD does that mean I have a paraesophageal hernia?

Often, patients with hiatal hernia also have heartburn or GERD. Although there appears to be a link, one condition does not always cause the other and the severity of GERD does not necessarily mean that there is a hernia. Many people also suffer from gastroesophageal reflux disease without having a hiatal hernia.

Are paraesophageal hernias dangerous?

Paraesophageal

Although paraesophageal hernias are less common, they are more cause for concern. Because the esophagus and part of the stomach stay in their normal locations, the herniated portion of the stomach which is squeezed through the hiatus may have a portion of its blood supply choked off. This condition is known as incarceration with strangulation.

When the blood supply is compromised, necrosis and perforation may occur; the mortality rate at this stage approaches 50%. The chronic squeezing and twisting of the stomach may also cause severe irritation of the lining of the stomach resulting in intestinal bleeding. Bleeding, although infrequent, occurs from gastric ulceration, gastritis, or erosions (Cameron lesions) within the incarcerated hernia pouch.

What causes a paraesophageal hernia?

Most of the time, the cause is not known. Some experts suspect that increased pressure in the abdomen from coughing, straining during bowel movements, pregnancy and delivery, or substantial weight gain may contribute to the development of a hiatal hernia. The repetitive stress of swallowing as well as that associated with abdominal straining and episodes of vomiting subject the membranes that make of the hiatus to substantial wear and tear, making it a possible target of age-related degeneration.

Another potential source of stress on the membranes is continuous contraction of the esophageal muscle induced by gastroesophageal reflux and mucosal acidification. In addition to the increased occurrence in people over fifty, hiatal hernias also occur more often in overweight people (especially women) and smokers.

Diagnosis

Paraesophageal

A hiatal hernia can be diagnosed with a specialized X-ray study that allows visualization of the esophagus (barium swallow) or with endoscopy. Paraesophageal hernias are best diagnosed with a barium swallow, although their presence is usually suggested by endoscopy that is being performed routinely for unrelated symptoms. In instances of paraesophageal hernia involving organs other than just the stomach, a definitive diagnosis is established with CT or MRI.

An upright radiograph of the thorax may be diagnostic, revealing a retrocardiac air-fluid level within a paraesophageal hernia or intrathoracic stomach. Barium upper-gastrointestinal series establishes the diagnosis with greater accuracy and helps distinguish a sliding from a paraesophageal hernia.

Upper endoscopy is used to diagnose complications such as erosive esophagitis, ulcers, Barrett’s esophagus and/or tumor. A hiatal hernia is confirmed by endoscopy on retroflexed views once inside the stomach. Preoperative testing will usually encompass esophageal manometry for evaluation of esophageal motility disorders, measurement of esophageal body peristalsis as well as measurement of the lower esophageal sphincter position, length, and pressures.

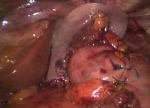

Surgical Treatment

Traditionally most surgeons believed that all paraesophageal hernias should be corrected electively on diagnosis, irrespective of symptoms, to prevent the development of complications and to avoid the risk of emergency surgery and very high mortality associated with strangulated paraesophageal hernias. However, recent evidence suggests that nonoperative management of asymptomatic patients might be a reasonable alternative.

Surgical repair of paraesophageal hernia is generally recommended for symptomatic patients however the operative strategy remains a matter of debate, and there is not a single technique guaranteeing uniform long term success. There are several controversies regarding laparoscopic/robotic repair for paraesophageal hiatal hernias. These include the necessity of excising the hernia sac, the best technique for closing the diaphragm (what type of mesh and whether to use mesh at all), the requirement of an antireflux procedure, and the need to perform a gastropexy (fixing the stomach to the diaphragm). The reported recurrence rate for laparoscopic/robotic repair has varies widely depending on the use of sequential postoperative xray contrast studies.

What to Expect

Traditionally most surgeons believed that all paraesophageal hernias should be corrected electively on diagnosis, irrespective of symptoms, to prevent the development of complications and to avoid the risk of emergency surgery and very high mortality associated with strangulated paraesophageal hernias. However, recent evidence suggests that nonoperative management of asymptomatic patients might be a reasonable alternative.

Dr. Belsley performs paraesophageal hernia repair with a combination of laparoscopic and robotic technology in order to ensure the best technical fixation of the mesh to the diaphragmatic defect. The antireflux procedure is determined by the intraoperative need to displace the gastroesophageal junction during reduction of the hernia as well as preoperative studies. An allograft mesh is typically used to buttress the repair depending on the size of the defect. Patients typically stay in the hospital for one or two days and then return home on a soft diet for the next two weeks.