What is done to my intestines during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy?

Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy requires changing the stomach from the size of a football to the size and shape of a banana. A small gastric reservoir is created that reduces the stomach size to 60-150 ml.

The operation involves the removal of the upper rounded part of your stomach called the fundus. The fundus is one of the parts of the stomach that produces ghrelin, the hormone that controls your appetite. While not yet completely understood, the removal of the fundus during sleeve gastrectomy seems to be one of the reasons why a sleeve gastrectomy is not just a restrictive procedure.

Sleeve Gastrectomy preserves many of your natural anatomic structures and connections including the antrum and pylorus along with vagus nerve innervation. Approximately 75%–80% of the greater curvature is excised, leaving a narrow stomach tube.

Surgical Steps of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

To gain access to the abdominal cavity, small incisions are created on the abdominal wall. Trocars, which serve as passageways for the surgical instruments, are placed through these skin incisions. Surgical instruments are passed through the trocars to access the abdominal cavity. The abdomen is filled with carbon dioxide (CO2) gas to lift the stomach wall away from the small intestine and other organs. The surgeon examines the abdominal cavity using the laparoscope which is a specialized video camera.

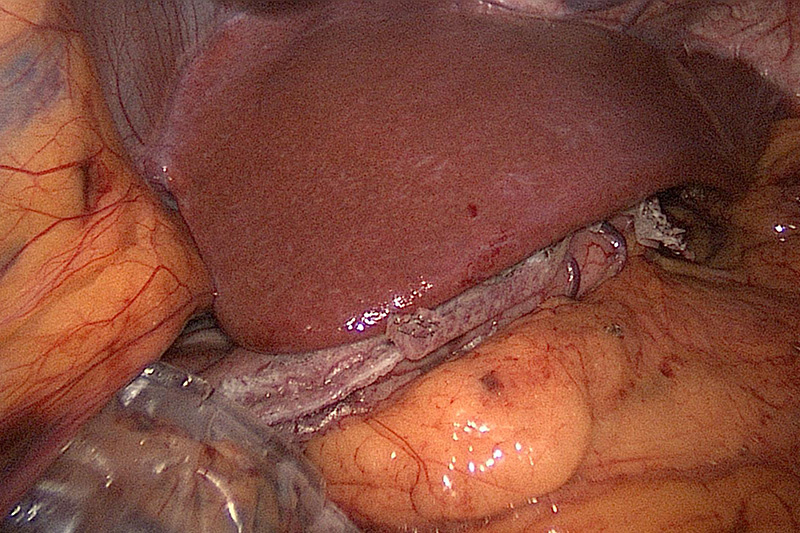

One of the first steps of the operation is positioning the liver. The edge of your liver sits directly over part of your esophagus and the first portion of the stomach. A retractor is placed which lifts the liver off of your stomach. This ensures that the whole stomach is adequately seen during the sleeve gastrectomy.

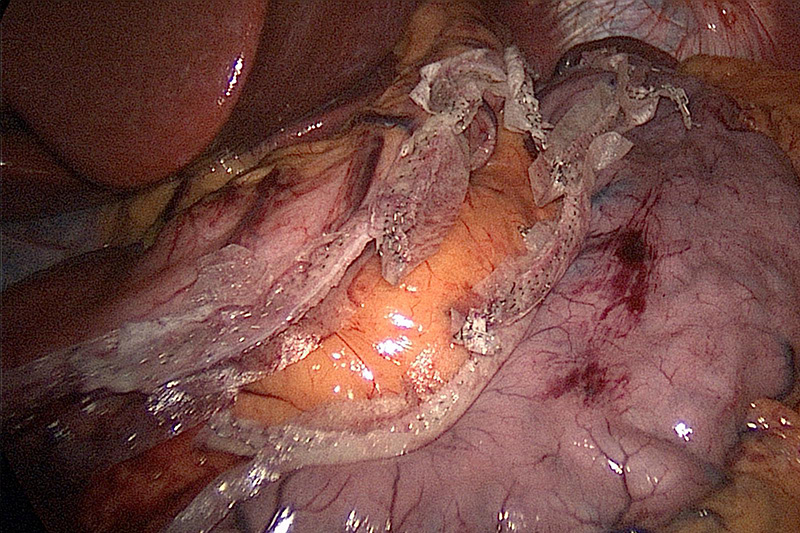

The tissue that attaches the stomach to the omentum is then separated so that the area under the stomach can be visualized. This allows the surgeon to have a view of the space behind the stomach. There are many important organs that lie below this part of the stomach including the pancreas and spleen.

The surgeon then continues to cut and seal these attachments and small blood vessels that lie on the larger side of the stomach, known as the greater curvature. This ligation of blood vessels and tissues continues along almost the entire length of this curve of your stomach extending from your esophagus to close to the area where the stomach attaches to the first part of your small intestines, the duodenum.

This separation of tissue requires the recognition of many anatomic landmarks. The dissection is carried from the tissue at the junction of the lower esophageal sphincter, the gastroesophageal junction in an area known as the angle of His. The angle of His is the acute angle created between the first part of the stomach at the entrance to the stomach and the esophagus. The angle of His has been implicated in reflux disease. This angle is opened up almost completely during sleeve gastrectomy and is therefore rendered irrelevant.

Greater curvature ligaments, the fibrous tissue that connects stomach and spleen (gastrosplenic), and stomach and large intestine (gastrocolic), are divided. The stomach is fully separated from spleen and bowels. The entire underside of the stomach from the greater curvature must be completely free from all the attachments up to the left crus of the diaphragm i.e. structures that attach the diaphragm to the vertebral column. The blood supply on the left side of the stomach as well as the left branch of the vagus nerve remains preserved.

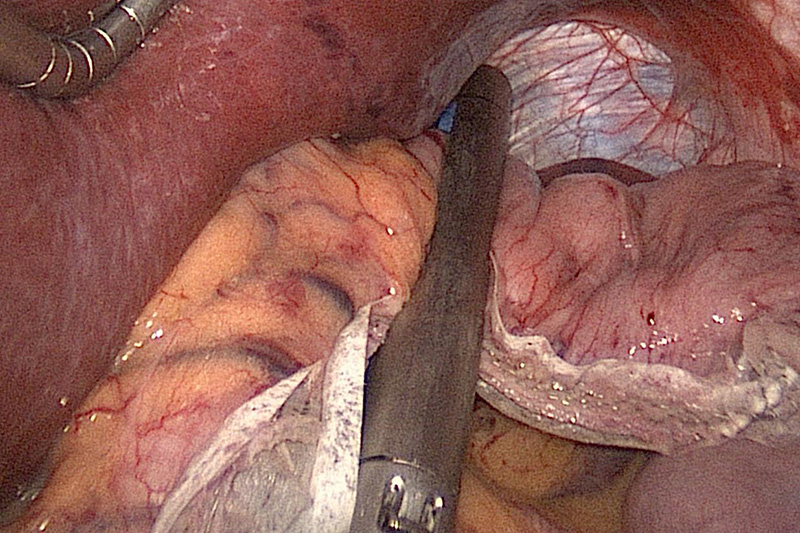

Separating the stomach by Stapling near the Angle of His

The surgeon then checks for the presence of hiatal hernia, the protrusion of the upper part of the stomach into the thorax through an opening in the diaphragm. If hiatal hernia is present, the defect is closed with sutures anterior to the esophagus and possibly posterior as well.

After the pylorus, part of the stomach that connects to the duodenum, is identified and the greater curve of the stomach is elevated. The surgeon then enters the lesser sac, the general cavity of the abdomen by entering the division of the greater omentum.

A sizing device called a bougie is then placed into the pyloric channel. The thick antrum or cavity of the stomach is divided by cutting transversely around the bougie to create a gastric tube. The pylorus, the valve that regulates emptying of the stomach, is spared along with a portion of the antrum ensuring preserved gastric emptying. The stomach is divided up to the level of the gastroesophageal junction, the lower part of the esophagus that connects to the stomach.

Judging the size of a Sleeve Gastrectomy

A gastric sleeve is a pouch with an estimated capacity of less than 150 ml. Stapling along the length of the stomach formed by the bougie creates a narrow tube. The staple line may be covered with material that is meant to reduce the risk of bleeding and/or leaks.

Extra care is taken to avoid relative narrowing at the junction between the vertical and horizontal parts of the stomach in an area of a notch, the incisura angularis. Your stomach is completely divided during sleeve gastrectomy. The entire staple line is inspected for bleeding and visually inspected for dysfunctional staples or a leak.

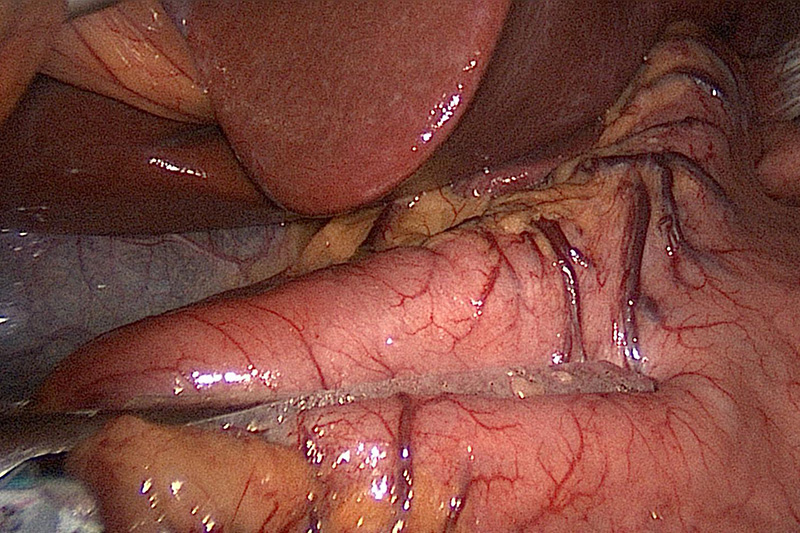

Sleeve Gastrectomy Demonstrating Divided Stomach

The resected stomach is placed in a specimen bag and then extracted through the trocar site. The remaining portion of your stomach would be the size and shape of a banana. The port sites are then closed with nonabsorbable sutures to prevent port site hernia.

Laparoscopic Gastric Sleeve is becoming more popular whether as a primary, staged, or revisional operation. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is now an established stand-alone bariatric procedure worldwide.

Sleeve Gastrectomy Shown Under Liver Edge