What is done to my intestines during Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery?

In laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery, the surgeon cuts across the top of your stomach, sealing it off from the rest of your stomach. The resulting pouch or bag can only hold about 1 to 2 ounces of food, and the stomach is reduced from the size of a football to the size of an egg. This stomach reduction is very significant as the normal stomach can typically hold about 48 ounces or 3 pounds of food.

This new stomach pouch is then attached to a piece of cut small intestine that is connected directly onto the pouch. When you eat after a gastric bypass, food enters into this small pouch of stomach and then passes directly into your small intestine. Food bypasses most of your stomach and the first section of your small intestine, and instead enters directly into the middle part of your small intestine. This results in fewer amounts of food intake and less absorption of calories leading to weight loss. The gastric bypass essentially creates two channels in the intestinal tract - one for the food and a second for the digestive juices.

Surgical Steps of the Procedure

Small incisions are made on the abdominal wall to get into the abdominal cavity. Trocars, medical devices that allow easy exchange of surgical tools, are then passed through the incisions to optimally access the abdominal cavity. The abdomen is then blown up like a balloon with carbon dioxide (CO2) gas which causes abdomen to swell and lifts your stomach wall away from the small intestine and other organs. This also helps the surgeon to view the abdominal structures and organs clearly using the laparoscope or video camera.

The first part of the operation involves mobilizing the omentum (double layer of fatty tissue that covers and supports the intestines and organs in the lower abdominal area) and the transverse colon (the part of the large intestine that hat lies across the upper part of the abdominal cavity. These structures are lifted towards the head to identify and open the ligament of Trietz, which is a small muscle that connects the duodenum to the diaphragm. The surgeon then lifts the transverse mesocolon (peritoneal fold that connects the transverse colon to the abdominal cavity) and creates a window. This lets the undersurface of your stomach be visualized.

Dividing and Moving the Intestine

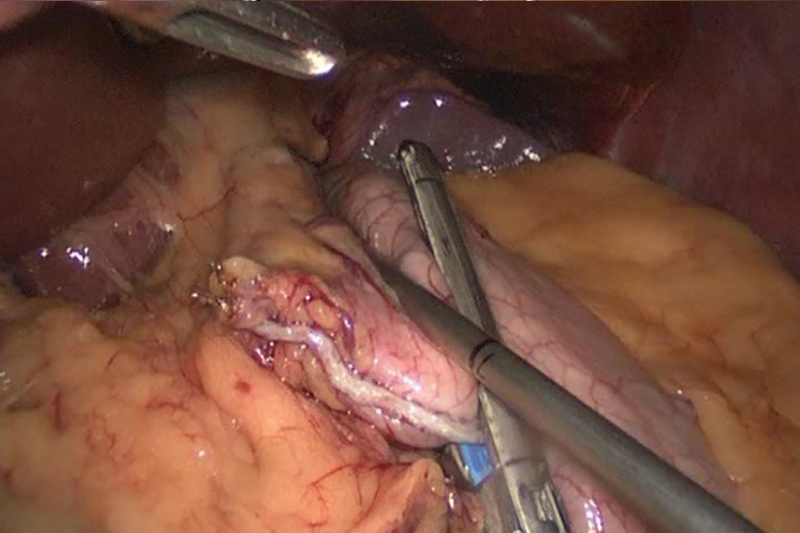

The next step involves dividing the jejunum (middle part of the small intestine) into two sections, the biliopancreatic limb and the Roux-limb which will later become the alimentary limb. The Roux-limb is the longer portion of your jejunum and is called the alimentary limb because it will be attached to your stomach pouch. The biliopancreatic limb is also called the biliary limb. This limb is the shorter part of the jejunum that remains attached to the remainder of your old stomach as well as your bile tubes.

Once the intestines have been divided, the next step is to measure somewhere between 100 cm and 150 cm of jejunum (middle part of the small intestine) further along in your digestive tract. This measuring will decide how long that your alimentary limb will be.

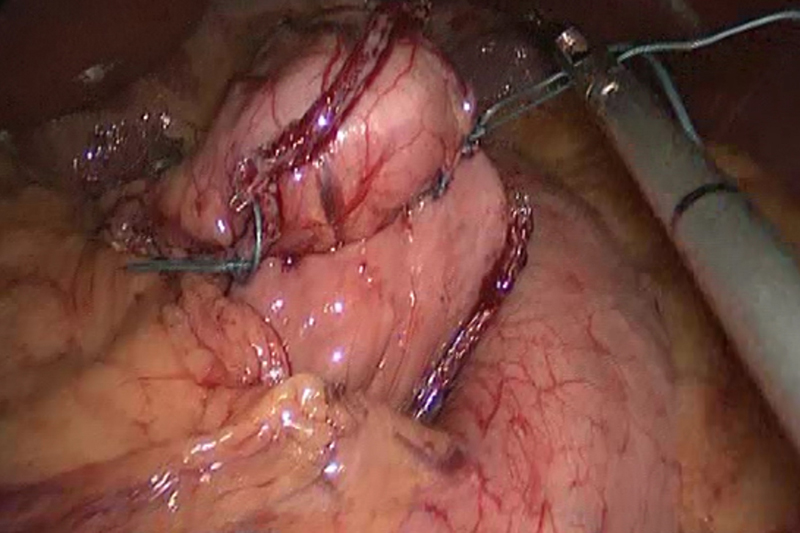

The shorter part of your jejunum is sewn and connected to the longer portion in the location just measured out. The surgeon then creates what is called an anastomosis. An anastomosis is a medical term for connecting two things together in the body. In this situation, the anastomosis is called a jejunojejunostomy because the connection represents two pieces of jejunum put together. The small intestine is connected to each other i.e. the biliopancreatic limb is connected to the distal end of the Roux limb. This connection is typically created by a combination of stapling and suturing. The mesenteric defect under the jejunojejunostomy is closed with a suture to prevent the development of an internal hernia. The small intestine is then placed behind the colon to where it is going to eventually being connected to the stomach pouch.

Creating the Gastric Pouch

In the next step, the stomach is divided about 1-2 inches below the area where the esophagus connects to the stomach by creating a window in the clear space of the gastrohepatic ligament (the structure that connects stomach to the liver). Once the lesser curvature of stomach is reached, a space behind the stomach is created that provides access into the lesser sac. The stomach is further divided with stapling to create a completely divided separate section. This smaller upper section of your stomach that remains connected to the esophagus is your new stomach, also known as the gastric pouch. This new gastric pouch has the capacity to hold approximately 1 to 2 ounces of food.

Laparoscopic Handsewn Gastrojejunostomy

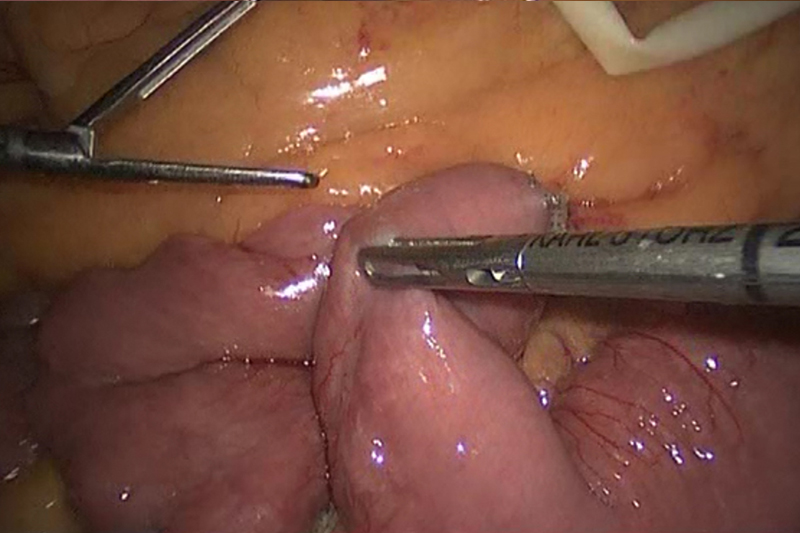

After creating a gastric pouch, the remaining part of your jejunum (Roux limb) is pulled behind the colon and behind the old portion of your stomach in order to be attached to your gastric pouch. The jejunum is either stapled or laparoscopically hand sewn to the stomach in one or two layers. The opening between the gastric pouch and the intestine is approximately 1 cm. Any redundant Roux limb is then reduced. Sutures are then placed in an interrupted fashion closing both the Petersen’s defect (a space between the roux limb and the transverse mesocolon) and the mesocolon (peritoneal fold that connects the large intestine to the abdominal cavity).

The new connections are then tested to be secure and a leak test is typically performed. The surgical instruments are removed and the incisions are closed with sutures. Your anesthesia is then stopped so that you can wake up after few minutes after your surgery is finished.