Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy

The esophagus is essentially a tube 1-2 inches in diameter (2-4 cm) that runs about 10 inches (25 cm) from the back of the mouth to the top of the stomach. Its job is moving food and liquid to the stomach, which it does largely by means of specialized muscles that push material down the pipe with synchronized contractions called peristalsis. It’s the same motion used in the intestines for much the same purpose.

Esophagectomy Specimen Removed for Cancer

The esophagus is a relatively simple organ but it does have several locations where problems are more likely. The most problematic area is at the bottom (technically, in the lower thoracic section) where the esophagus connects with the stomach – the gastroesophageal junction. At the junction is the lower gastroesophageal sphincter, a hole into the stomach controlled by a set of muscles that opens to allow food to enter the stomach, and closes to prevent stomach acid from entering the esophagus. When this sphincter is not functioning properly, especially as a chronic long-term condition, there are many potential problems, some of which may lead to cancer.

At the top of the esophagus (in the cervical section), where it meets the back of the mouth at the area called the pharynx, there is the upper esophageal sphincter, which prevents food and liquid from entering the esophagus without the action of swallowing. Just beyond is the epiglottis, a flap of cartilage tissue that works in concert with the act of swallowing to keep food and liquid from going down the windpipe (trachea). This area is subject to inflammation, which we know as a ‘sore throat’ and can be the location of other serious conditions.

Between top and bottom, the pathway of the esophagus is relatively straightforward. However, from a surgical point of view, there are two areas with complications: The section where the esophagus passes behind the heart and major heart blood vessels, and the point where it passes through the diaphragm, the muscle layer separating the thoracic cavity with the heart and lungs and the abdominal cavity. Each of these may be significant for an esophagectomy.

Diseases that may lead to an esophagectomy

As might be expected, many of the problems of the esophagus relate to food, drink and smoke – the things people ingest. Smoking tobacco in particular is high on the list of causes for many diseases in the esophagus, especially cancer, followed by alcohol consumption and over-eating certain acidic foods.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Gastroesophageal Reflud Disease or GERD is by far the most common problem with the esophagus occurs at or just above the lower esophageal sphincter. Medications, pain relieving drugs, and loss of muscle tone may cause the sphincter to work improperly. When it does, gastric fluids (acids, enzymes and bile) from the stomach may flow into the esophagus. We know this as heartburn, or these days as acid reflux, for which over-the-counter medicine is available. Many people experience acid reflux – for example, from lying down after eating too much – but this is occasional and temporary (transient). If acid reflux persists and occurs frequently, the stomach fluid damages the lining of the esophagus. This may lead to many conditions but notably for the development of Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus

When stomach fluid repeatedly damages the lining of the esophagus, it causes changes in the esophagus cells. In 5-8% of GERD cases, this becomes Barrett’s esophagus which is a condition of the esophagus lining where the tissue cells are genetically unstable and prone to mutation. About 0.5% of Barrett’s esophagus leads to dysplasia. Dysplasia is a precursor to cancer. These percentages may seem small, but chronic acid reflux affects millions of people.

Cancers of the esophagus

The dysplasia associated with Barrett’s esophagus can become adenocarcinoma, a cancer that originates in the glandular cells around the gastroesophageal junction. It has the notoriety of being one of the most rapidly proliferating types of cancer in the world. In the United States, it accounts for 50-80% of esophageal cancer cases.

Adenocarcinoma may be either benign or malignant; however, as the tumors grow they typically pose problems by blocking the esophagus and cause considerable pain in the chest region. Unfortunately, many cases are not diagnosed until a later stage (III or IV) when the blockage of the esophagus is sufficient to cause problems with swallowing and digestion. By this time, the tumor is generally large and the primary treatment becomes removal of a section of the esophagus and surrounding tissue – an esophagectomy.

Squamous cell cancer

is the second type common to the esophagus. It accounts for about 90% of esophageal cancer worldwide (less so in developed countries). Unlike adenocarcinoma, which is usually located in the lower thoracic section of the esophagus, squamous cell cancer typically affects the upper thoracic and cervical sections. This belies two of its common causes – smoking and drinking (alcoholic beverages). Again as the tumor increases in size, it may affect swallowing. With the location higher in the esophagus, a squamous cell tumor may also affect breathing, blood flow from the heart and movement in the neck. For larger tumors, an esophagectomy is often the primary recourse.

How will you know when an esophagectomy is required?

Unfortunately, for esophageal cancer, by the time patients seek medical help, they are usually well aware of painful and difficult swallowing caused by a tumor. They may already be limiting the amount of food they eat and taking mostly liquids or soft foods, often accompanied by lack of hunger, poor nutrition and weight loss. Sometimes the location of the tumor causes nausea, bleeding, severe cough and pain in the upper chest. Of course, these symptoms are not unique to esophageal cancer, but the location and association with swallowing and digestion are strong clues for the diagnosing physician.

With suspected esophageal cancer, the first step in confirming the diagnosis is usually examination by endoscopy, sending a flexible tube with camera and light down the esophagus. The condition of the wall of the esophagus, areas of blockage and the presence of lesions are enough to call for tissue biopsy to test for malignancy.

Minimally Invasive Gastric Pull-up for Esophageal Reconstruction

Once confirmed, the diagnosis of cancer leads to one or more scans to determine the extent and nature of the cancer. This may involve a computed tomographic (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis to see if the cancer has metastasized to other organs – especially the liver and lymph nodes. Positron emission tomography (PET scan) may obtain a more precise image of the cancer. An endoscopic ultrasound of the esophagus may reveal more information useful for staging, the level of tumor invasion, and the spread of cancer to lymph nodes in the area.

Combining the scanned images with laboratory results, the diagnosing physician can usually identify the type of cancer and arrive at a close estimate of the cancer stage. The staging of cancer, with identification of how far the cancer has progressed in stages I through IV (with numerous sub-stages), is crucial to determining the course of treatment.

As with most cancers, there are a variety of possible treatments including radiology, chemotherapy and surgery. Because diagnosis of esophageal cancer tends to happen late in the cancer’s development, when the tumor is already quite large, a relatively high percentage of treatments involve removal of a section of the esophagus and often much of the surrounding tissue, especially lymph nodes.

Not all patients are candidates for this operation. As with all operations of this magnitude, a very thorough risk assessment considers the patient’s age, general condition, the stage of the cancer and any other complications to the surgery. Selection of the esophagectomy procedure is a crucial part of this risk assessment.

There are several surgical options

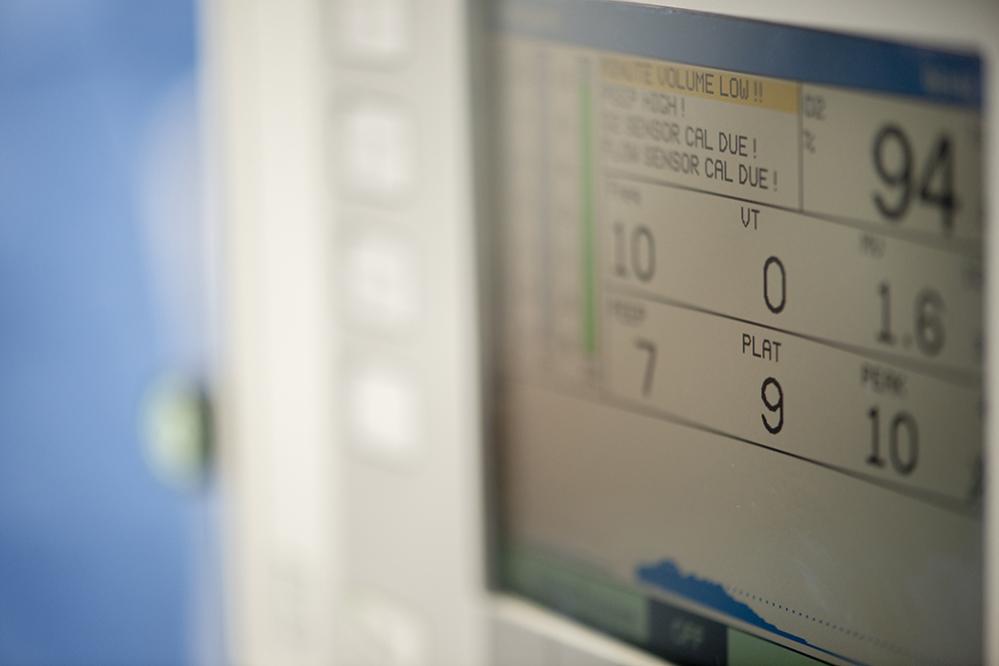

An esophagectomy is a complex operation that usually requires several hours to perform. Management of airways and lung functioning, with the threat of lung collapse, is a significant concern during the operation and contributes to the difficulty of anesthesiology for the procedure. Likewise, the extent and duration of the operation may also affect the function of the diaphragm (recall that the esophagus crosses the diaphragm) and the spleen. Major complications occur in 10-20% of patients, which makes it desirable to limit the impact of the surgical procedure.

Very often esophagectomies require two major phases: The removal (resection) of a portion of the esophagus and often surrounding tissue (especially lymph nodes), and the rebuilding of the esophagus, often by stretching a portion of the stomach or by grafting tissue from the colon, in the process of anastomosis, joining the replacement segment of the esophagus with the old.

One traditional approach to removing a portion of the esophagus, the transthoracic esophagectomy(TTE), is an open form of surgery, meaning surgeons cut large incisions to expose the relevant areas. In TTE, the procedure opens a major segment of the chest (thorax). A similar procedure, the trans-hiatal esophagectomy (THE), makes open incisions on the neck and abdomen simultaneously. Both approaches provide the surgeon with a relatively clear field of operation (i.e. they can directly see and manipulate the tissue), but for the patient the extent of trauma is considerable and recovery can be lengthy.

In roughly the past twenty years, the effort to decrease surgical trauma during esophagectomy resulted in the application of minimally invasive surgery (MIS)techniques. There are several variations, but in essence each of them seeks to reduce the size and number of incisions, perform the surgery using thorascopy or laparoscopy (video assisted), and reduce complications from infection and inflammation associated with the large surgical cuts of traditional open operations.

For those patients fortunate to have their diagnosis while in the early stages (I and II), some may be candidates for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), where a light, video camera and surgical tools are mounted on a tube and sent down the esophagus to remove small lesions or other cancerous formations on the walls of the esophagus. This is essentially the same technique used to make biopsies of the esophagus and by definition is minimally invasive.

Minimally invasive esophagectomy

Minimally invasive surgery adjusts the procedure to the location and size of the cancer tissue and the source of replacement tissue for rebuilding the esophagus. There are two main approaches: Ivor Lewis esophagectomy and the “Three Hole” or McKeown esophagectomy. Esophagectomy is a complex procedure performed by surgical teams, minimally with one primary or specialist surgeon (possibly one laparoscopic and one thorascopic surgeon), a surgical first assistant, and a laparoscopic/thorascopic camera specialist. Surgical teams tend to use one or the other of the basic approaches and then make variations, depending on the surgeon’s preferences and the patient’s requirements.

One of the most popular of the MIE approaches, Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, is a two-stage operation, sometimes called a thoracolaparoscopic esophagectomy (TLE), involving thorascopy and laparoscopy.

Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy Requires Specialty Collaboration

While the order of steps and the details differ among surgical teams, the first phase of the operation begins with creating laparoscopic access to the area of the stomach and the lower portion of the esophagus. A number of small incisions called ports provide access for laparoscopic tools while exposing a minimum of underlying tissue. One port creates access for the laparoscope, which provides the view of the operating area on one or more monitors. Other ports introduce trocars with surgical tools.

The main task of this phase is to fashion a gastric conduit as a replacement for the segment of the esophagus to be removed. Often this conduit is created by extending stomach tissue, or cut from the upper intestine (jejunum). This phase usually includes preparation of the stomach for the replacement gastric tube, which will be attached (anastomosis) with staples.

The second stage of the operation creates the thorascopic (chest) ports to access an upper portion of the esophagus with the principle task of removing (resection) a segment of the esophagus and any surrounding tissue affected by cancer (including lymphectomy to remove cancerous lymph nodes). Once cancer tissue is removed, the upper end of the replacement gastric tube is pulled into position and stapled into the remaining upper portion of the esophagus. The operation concludes with the reconnection of freed tissues, opening of blood vessels and eventual closing of the operating ports.

What is the surgical follow-up and continued treatment?

Recovery from a minimally invasive esophagectomy is considerably faster on average than for traditional open surgery, meaning weeks instead of months in most cases. Nevertheless, post-operative complications are relatively common and range from bleeding around the replacement esophagus segment to difficulties with lung function and surgical spreading of metastatic cancer elements (seeding) leading to a reoccurrence of the cancer. It is common for a continuation of chemotherapy or radiological treatment as follow-up to the esophagectomy, along with a life-long monitoring of diet, life-style and digestive condition.

The prognosis for minimally invasive esophagectomy

The success of minimally invasive esophagectomy, as is the case for all forms of cancer surgery, is very much a function of the patient’s overall age and health, plus the stage of the cancer. Various studies place the 5-year survival rate around 70% for Stage 0, 65% for Stage I, 34% in Stage IB, 20% for Stage II, 14% for Stage IVA and 5.5% for Stage IVB.

Over the last decade, minimally invasive esophagectomy has proven to be practical and safe for a wide variety of esophageal cancer cases, as well as a number of non-cancer conditions such as removal of physically damaged areas of the esophagus. It remains most effective for earlier stage cancer, up to Stage II and sometimes Stage III.