What is your spleen and why is splenectomy needed?

Almost everybody knows they have a spleen but few can tell you what it does. Perhaps that’s because it’s not a vital organ – you can live without one. The spleen is normally a fist size organ located in the upper left abdomen near the stomach and pancreas.

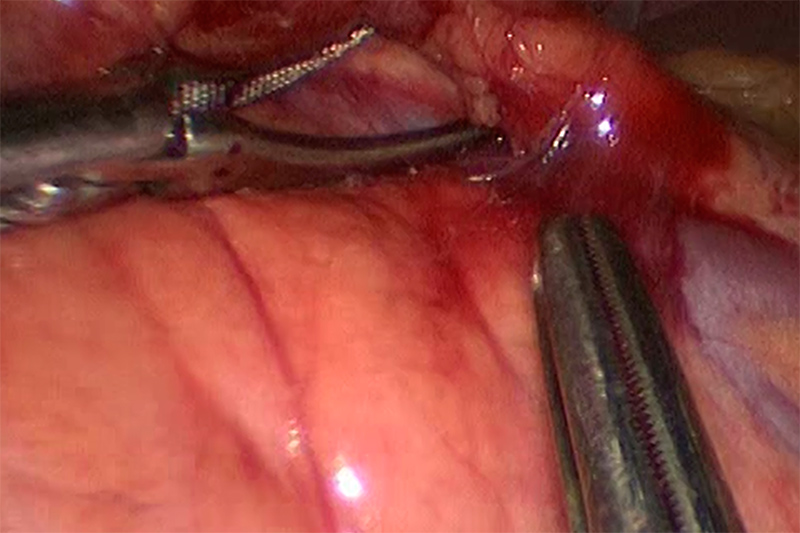

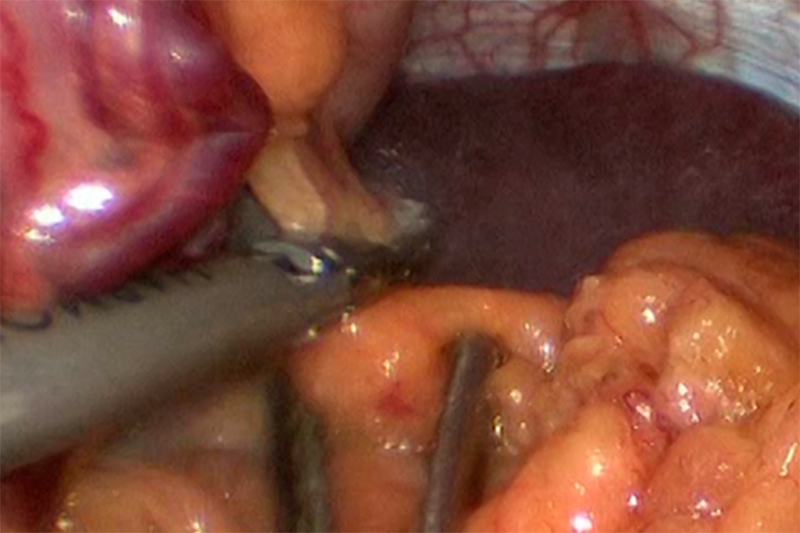

Splenectomy Requires Meticulous Dissection

Functionally, it is an organ of the blood, although technically it is part of the lymphatic system. Part of it, the red pulp, plays a major role in the regulation and storage of platelets (the blood component involved in coagulation). This part of the spleen also regulates the condition of red blood cells, removing the cells that are dead or defective. In this sense, the spleen is a blood filter. The white pulp area of the spleen has a similar function with white blood cells.

This is where macrophages, cells of the immune system, remove and destroy white blood cells with bacteria. This part of the spleen is like a large lymph node.

Essentially, the spleen is a filter and regulator. As such, when things go wrong with the spleen it’s usually in reaction to damage or disease elsewhere in the body.

What are conditions that may lead to a splenectomy?

The list of diseases that have serious impact on the spleen is very long, in fact; it could be almost any disease involving the blood, to name a few: Malaria, sickle cell anemia, leukemia, pernicious anemia, Hodgkin’s disease, mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus, sarcoidosis, tumors and cysts.

Typically, these diseases cause the spleen to become very active. When it does, it processes and stores more blood, which causes it to enlarge. To a certain extent, the enlargement is normal and disappears when the disease causing it goes away. However, sometimes the disease gets worse or the spleen itself overreacts and a condition called splenomegaly(spleen-oh-MEG-allee), a chronically oversized spleen develops.

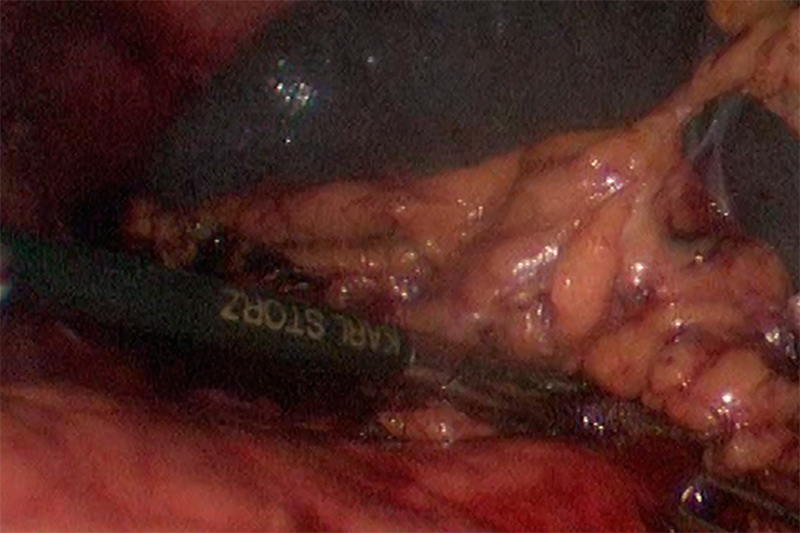

Ligation of the Polar Arteries

Occasionally, the enlargement is so great – massive splenomegaly – that the spleen pushes against nearby organs such as the stomach and related arteries. This can cause enough problems that removal of the spleen may be the only solution. More commonly, however, the enlargement of the spleen presents a different kind of problem – it’s working too well.

As mentioned, one of the functions of the spleen is regulation of blood platelets. There are a number of diseases; idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is the most relevant example, which causes a deficiency in blood platelets. If untreated, ITP may eventually lead to internal bleeding, even death. The spleen reacts because ITP changes the chemistry of platelets, which makes them a target for removal by macrophages in the spleen. The spleen makes the platelet shortage even worse, so much so that one of the ways to improve the platelet count is to remove the spleen.

Something similar happens with hemolytic anemia, a disease that breaks down red blood cells – damaging them so much that the spleen attempts to remove too many red blood cells from the blood – making the anemia worse. Removal of the spleen, a splenectomy, can reduce the need for continual transfusions to replace the red blood cells.

There are a few instances, often caused by tumors, where the blood supply to the spleen is partially or fully blocked (an infarct). When this happens, tissue in the spleen may die (become necrotic) and all or part of the spleen must be removed.

Like all internal organs, the spleen can be severely damaged physically, such as by a car accident or a fall. Sometimes when the damage is great or causes life threatening blood loss – given that the spleen is not a vital organ – doctors will call for a splenectomy.

There are not many diseases of the spleen itself, but the most common is a form of cancer, lymphoma. This is a disease of the lymphocytes, cells associated with the lymph system. As the spleen is part of that system, lymphoma elsewhere in the body can affect it (often causing splenomegaly) and it can develop its own form of cancer – splenetic lymphoma. Depending on the stage of cancer in the spleen, where chemotherapy or radiological treatment is of no avail, a splenectomy is the usual recourse.

How will you know if a splenectomy is required?

It’s not unusual for patients to be unaware of problems with the spleen. For one thing, those problems may be caused by more serious and obvious disorders elsewhere in the body. Unless the spleen is massively enlarged, splenomegaly may not be apparent to the touch nor cause any pain. Even lymphoma of the spleen may grow so slowly that it takes years or decades for it to become an acute problem.

However, with modern blood tests and the use of imaging equipment such as CT scans, ultrasound or MRI, physicians may detect problems with the spleen, often in connection with other disorders. In fact, one of the challenges for doctors is to determine where splenomegaly is a ‘normal’ response by the spleen to other illnesses or where the spleen itself is malfunctioning and a serious contributor to the problem – a situation that may call for a splenectomy.

The decision to recommend a splenectomy depends on many variables including overall patient health, age and physical condition, the nature of the disease causing the problem with the spleen, the size of the spleen (for massive splenomegaly), and the effectiveness of other treatments (e.g. for cancer).

What are the surgical options for removal of the spleen?

Until the advent of laparoscopic surgery, roughly beginning in the 1990’s, surgeons performed splenectomy through open surgery. As it sounds, open surgery means cutting one or more relatively large incisions in the abdomen, pulling back the layers of tissue to expose the spleen and surrounding organs. This approach to surgery is ‘traditional’ and sometimes preferred by surgeons because it provides maximum visual access and they can use their hands for immediate surgical response.

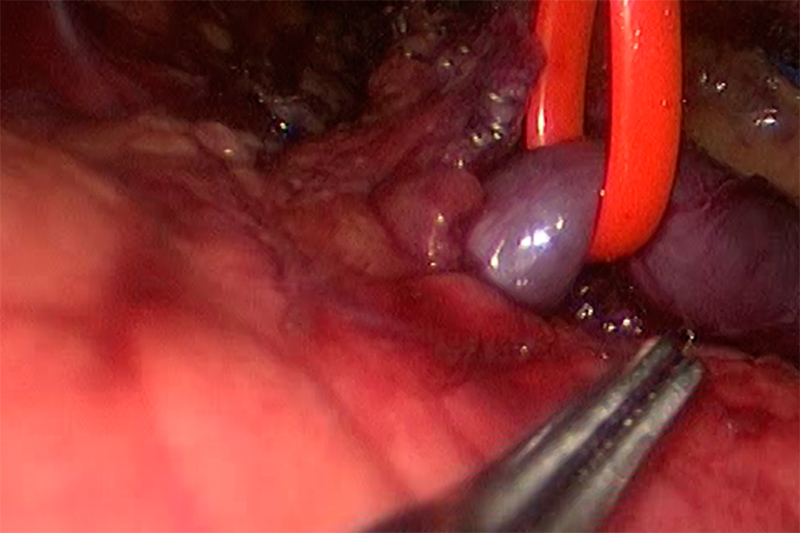

Multiple Ligaments Protect the Spleen

However, from the patient’s perspective, open surgery creates a great deal of trauma. The large incisions may cause a lot of pain, take long to heal and present risks of infection. Although it is accurate to say that laparoscopic surgery is now the standard procedure for splenectomy, open surgery is still appropriate for cases where morbid obesity, a history of abdominal surgery with dense scar tissue, or where there is great difficulty visualizing organs due to severe bleeding. There is also some controversy whether laparoscopic surgery is appropriate for massive splenomegaly, where the weight of the spleen exceeds 2,000 grams or the spleen is much larger than 20 centimeters.

Concern over the size of the spleen to be removed is obvious for laparoscopy. The essence of modern laparoscopy is to make as small incisions as possible. Actually, laparoscopic surgery creates ports, more like holes or channels in the skin and tissue than incisions. A trocar, a kind of hole-punching tool, creates the ports as access points to the underlying organs. Depending on the surgical team and the chosen laparoscopic technique, usually four or five ports suffice for a splenectomy, with one for the laparoscopic camera tube, and only one of any size (possibly a few centimeters) to allow for removal of spleen tissue.

The limited number and size of the ports highlight the advantages (for the patient) of laparoscopy:

- There is less postoperative pain due to less tissue trauma

- Shorter hospital stays are typical, often only a few days

- There is usually a faster return to normal diet

- A quick return to normal (if temporarily less vigorous) activity is desirable

- The cosmetic results are better, with surgical scars sometimes hardly visible

Removing the spleen by laparoscopy

A laparoscopic splenectomy is a team effort, minimally involving a surgeon (usually the primary or laparoscopic specialist), a surgeon first assistant and a camera assistant (a specialist who operates the laparoscopic camera).

Vessel ligation during Splenectomy

Removal of the spleen is a major operation with a number of pre-operative requirements, which may include:

- Vaccination for influenza, lung bacteria (pneumococcus), and meningitis

- Blood analysis, especially for platelet supply

- Chest X-ray, EKG, ultrasound or MRI to determine physical condition of the spleen

- Blood supply, especially platelets that may be needed for transfusion

- Patient stops taking certain medications, especially aspirin, blood thinners, diet medications

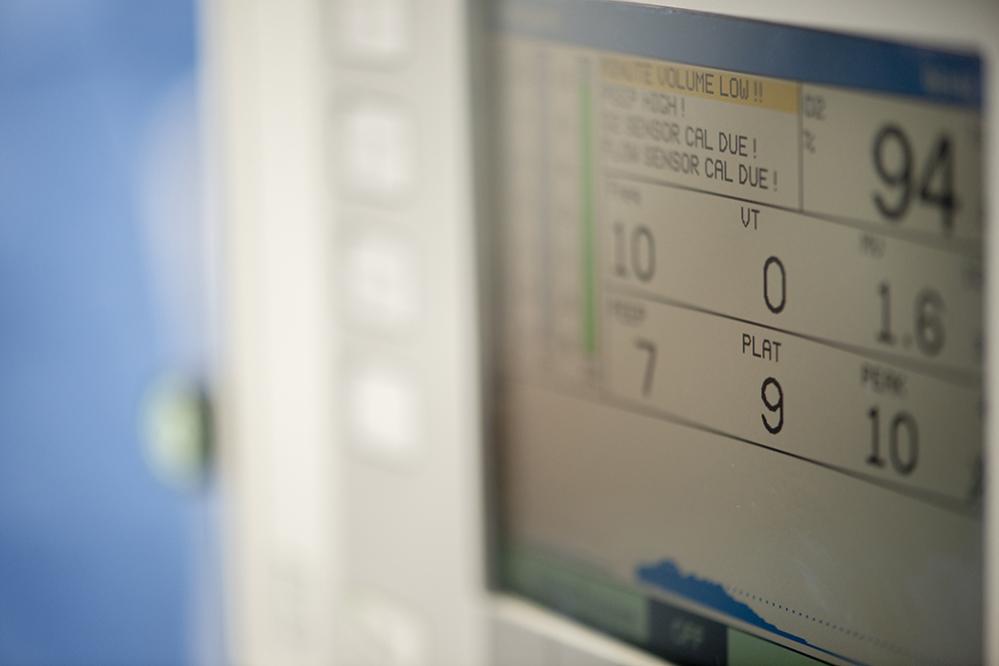

As with most major operations, the patient is under general anesthesia and completely asleep. The surgical team begins with opening a number of ports. As a rule, the first one is to inflate the abdomen with carbon dioxide, creating a working space around the spleen. Following this is a port for the laparoscope. Most surgical teams use the digital laparoscope with a CCD (Charged Couple Device) camera at the end of an optical fiber tube. Most ports are kept open with a cannula (operating tube) or special surgical gel.

The surgical team uses television monitors to see inside the abdomen with the laparoscope. The special skills for surgical movement, procedure management, and laparoscopic vision may require months of training, practice, and years to build experience.

Once the laparoscope and required surgical tools are in place, blood flow to the spleen is cut off by surgical ligature (stapling, tying off or clipping). One of the first procedures – somewhat surprisingly – is to remove ‘extra spleens.’ Roughly, 15% of all patients have small polyp-like spleen tissue growths, a condition called polysplenia. The main event cuts the spleen loose from the body (mobilizes it) and the tissue placed inside a small surgical bag. Pulling the bag up to the area near the largest port, the contents are squeezed (morcelated) to reduce the size in order to pull the bag through the incision.

Because the area of surgery (the surgical field) in a laparoscopic splenectomy is close to major arteries, the pancreas and the stomach, there is always the risk of damage. Occasionally conditions develop, such as intense bleeding, where the surgeon may call for a change in procedure and proceed to open surgery.

What happens after the surgery and when can the patient go home?

The post-operative period is typical of any major abdominal surgery. There is the time in a Postanesthesia Care Unit or possibly a critical care unit. An IV tube provides fluids, antibiotics and medication for pain.

Because the removal of the spleen leaves a temporary space in the abdomen, other organs, notably the stomach, adjust position. During this time, the fluids in the stomach may not empty properly, which may require a stomach tube (through the nose) to prevent vomiting or bleeding. Fluid may also accumulate in the space where the spleen used to occupy. This fluid is normal and will be reabsorbed by the body in a few weeks.

It may take several days in the hospital for the digestive system to normalize (more or less). The surgeon’s principal concern is with the possibility of internal bleeding, leakage from the surrounding organs, infection in and around the surgical ports, and the apparent rate of healing for the area of the operation. The surgeon and the primary physician will tell the patient when it is safe to go home.

The first days at home could be described as ‘normal – light.’ Activity such as walking, showering (no bathtub), cooking and light movement is recommended. Driving depends on the level of medication. Diet usually can quickly return to normal although there may be constipation.

The most important concern with post-operative splenectomy is the potential for long-term immune system and bacterial infection problems. The worst case, rare but possible, is Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection (OPSI), where a cascade of failures in the immune system may cause rapid and fatal infection. The potential for OPSI is lifelong, which means the people without a spleen (asplenetic) must be extremely aware of infections, inflammations and unusual physical changes in the area of the abdomen. Vaccination can somewhat lower the incidence of OPSI and antibiotics can often successfully treat OPSI and other immune system problems caused by a lack of a spleen, if a physician is consulted in time.

Because of its role in filtering the blood and as part of the immune system, people without a spleen need to be alert for conditions such as infections and inflammation, as the body is less able to resist certain bacteria and some vaccines are less effective.