How does the Gallbladder help Digest food?

To describe the role of the gallbladder in digestion, let’s start with what we eat. Human beings are omnivores; we’ll eat just about anything. We often eat meat and dairy products that contain a significant percentage of fats. These foods contain animal fats, which are complex as fats go and potentially contain a lot of useful energy. However, these fats are polyglycerides, which are forms of fat compounds with molecules so large that the body can’t use them. So, one of the jobs of digestion is to convert (emulsify) polyglycerides into much smaller monoglycerides that can be absorbed by the intestines and eventually turned into cellular energy.

The Gallbladder and Rich Foods

After breakdown by the acids in the stomach, what’s left of your meal enters the top of the small intestine at the duodenum. Here there is a hormone, cholecystokinin (CCK), which reacts to the presence of fats – the more fat, the more it reacts. The more it reacts, the stronger the signals it sends through the nervous system to the pancreas and gallbladder ordering them to deliver digestive bile.

Liver bile is what makes fat work for you

The bile from the gallbladder originates in the liver. It’s a greenish-to-brownish fluid composed of water, cholesterol, phospholipids (a type of fat), bile salts, proteins and bilirubin. Bilirubin is the product of hemoglobin breakdown in the liver and gives bile its yellowish color. The bile is also the medium for all the things the liver is trying to get rid of – toxins, excess cholesterol and impurities of one kind or another.

From the perspective of digestion the most important component of liver bile are bile salts, an umbrella name for a large family of acidic compounds that emulsify fats or make them water-soluble. Most of them are derivatives of cholesterol (cholic and chenodeoxycolic acids) that have amino acids added to them (glycine or taurine) to form taurocholic acid and glycocholic acid. They’re called “salts” because there is an extra positive ion attached to each molecule, which is usually sodium.

The bile salts have two main tasks; one is to emulsify large fat molecules into smaller, simpler fats; the other is to make the fats more water-soluble by forming micelles, aggregate drops of fatty acids, cholesterol and monoglycerides (those simple fats) dissolved in water for easy absorption by the intestine.

The transformation of fats by bile salts in the duodenum is also important for preparing fat-soluble vitamins to pass through the lining of the intestine into the bloodstream.

The liver produces between 400 and 800 milligrams of bile a day, most of which flows down the common duct to the top of the small intestine. When not receiving a stimulus from the CCK in the duodenum, which is pretty much the same as the time between meals (with a lag for digestion), the bile diverts to the gallbladder for storage.

The physical gallbladder

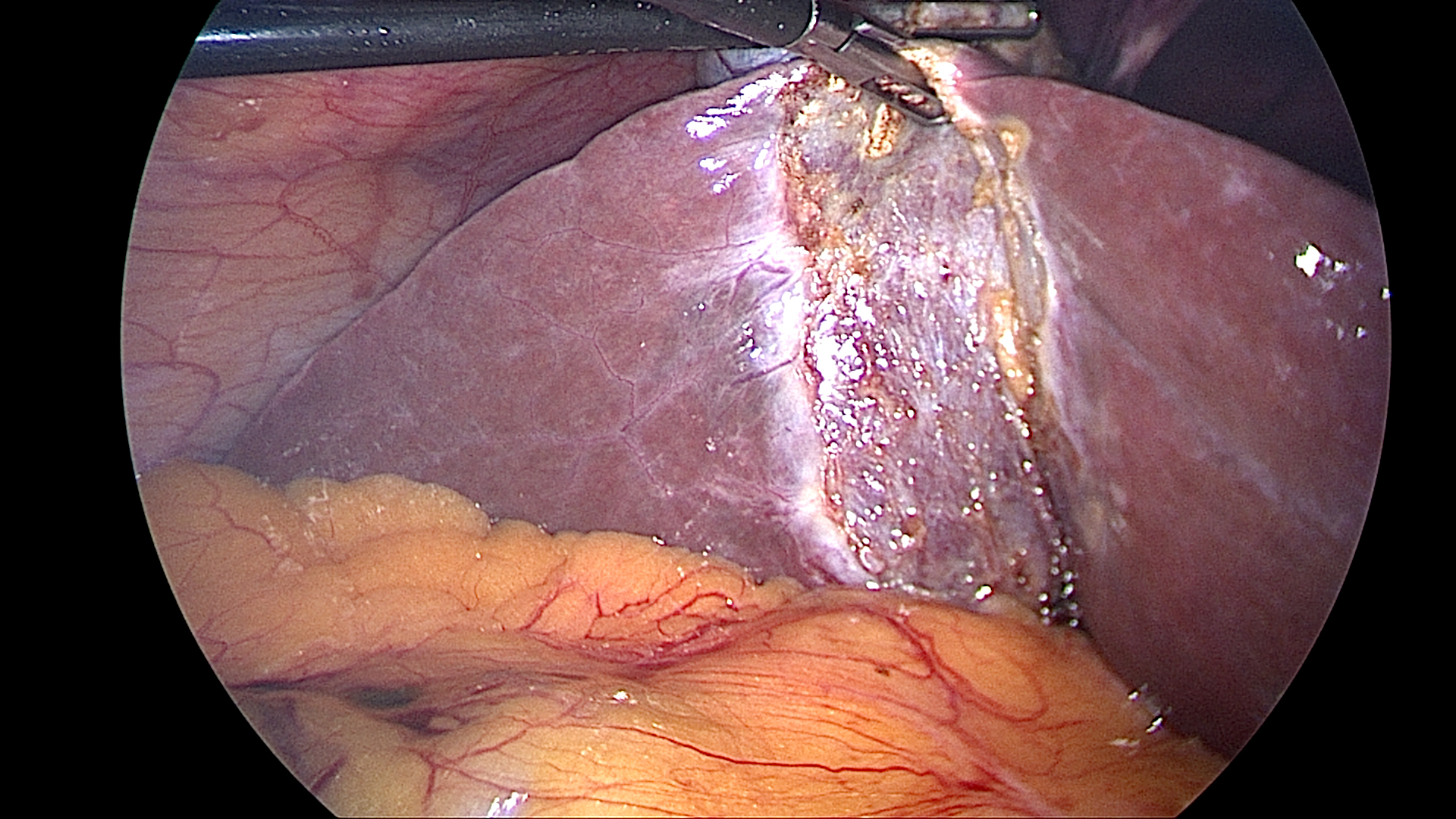

Gallbladder Retraction During Surgery

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ nestled under the liver and at about the same level as the lower stomach. It’s essentially a flexible pouch, able to expand in order to contain more bile but also with the ability to contract on signal to squeeze additional bile into the common bile duct. When full, it measures about 8 centimeters (3.1 inches) long by 4 centimeters (1.6 inches) in diameter – roughly the size of a small baking potato.

One of the functions of the gallbladder is to concentrate the bile produced by the liver. Mainly by removing water, the bile is reduced from a fifth to a tenth of its original volume until reaching the maximum capacity of the gallbladder at about 50 milliliters. This concentration is a kind of balancing act. If the gallbladder doesn’t concentrate the bile, then there may not be enough active ingredients to break down a heavy load of fat, resulting in digestive problems. If the gallbladder performs too much concentration, the lack of water may stimulate the formation of gallstones around impurities in the high saturation of cholesterol.

Gallstones are the bane of the gallbladder

Gallstones on CAT Scan

The fact of the matter is that many people have gallstones much of their adult lives and never know it. Typically, if there is going to be a problem with gallstones, it happens within the first 8-10 years of their formation. No one knows why this is so, but the older you get without gallstone problems; the less likely they are to occur. When they do occur with pain and inflammation (cholecystitis), the condition can be excruciating.

Most gallstones are composed of cholesterol although they can also be made from bilirubin or a mixture of cholesterol and other elements in the bile. They can range in size from a grain of sand to as large as a golf ball. Gallstones become particularly troublesome when they travel. They may move out of the gallbladder and travel down the common bile duct all the way to the junction with the pancreatic bile duct and beyond. However, they can and do become stuck and form a blockage. That can lead to pain, infection, lesions and even breakage of the duct. The condition is called choledocholithiasis and often requires medical treatment.

The bile salts recycling system (enterohepatic recirculation)

Because most of the digestive system operates outside our consciousness (unless there is something wrong), most people are unaware of the rather delicate sensory system involved in the process of digestion. Just the part that includes the gallbladder is a complex set of triggers (CCK, for example) and responses in the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, intestines and even the stomach and brain. We may be aware of some of this when we get the signals of hunger pangs.

One of the important systems maintains the supply and balance of the bile salts, which are produced by the liver in considerable quantity but only about 5% are lost through expulsion with feces. The rest of the bile salts are absorbed through the lining of the ileum (middle portion of the intestines), flushed into ileac vein straight into the portal vein of the liver and from there back into circulation for the creation of liver bile. Each bile salt may be recycled as many as twenty times and perhaps three times for each meal-digestive cycle.

Another digestive sensory system involves the hormone secretin, which is produced in the duodenum in response to the acid versus base level of the food mixture. When there is too little acid, secretin becomes the neurotransmitter that stimulates the common biliary duct to add more water and bicarbonate to the flow of bile and increasing the volume.

The central role of cholesterol

As you may have noticed, from the extraction of excess cholesterol by the liver and removing it through the bile, to the formation of gallstones, to the creation of the bile salts, cholesterol is a key ingredient in the role of the gallbladder in digestion. While there is still much research to be done, the outlines of the cholesterol metabolism in digestion are reasonably clear. Most of the body’s intake of cholesterol is processed and removed by the liver, much of it to fabricate the cholic acid and chenodeoxycolic acid elements of liver bile.

Interestingly, thus far research does not show strong correlation between diet, cholesterol levels in food, cholesterol levels in the blood and the incidence of cholesterol gallstones. On the other hand, studies have shown that people taking cholesterol-lowering drugs have a higher incidence of gallstones.

How is the amount of gallbladder contraction measured?

HIDA Scan

The gallbladder needs to contract after a fatty meal in order to release its concentrated bile into the digestive system. The messenger for this contraction is endogenous postprandial CCK. There are hypothetical abnormalities in the CCK-gallbladder relationship that can be quantitated using diagnostic imaging. The relevance of these measured abnormalities is unclear. Some authors have attributed an increased response to an increase chance of gallstone formation while others have found the opposite.

There is a condition known as biliary dyskinesia which is defined as symptoms consistent with gallstone pain but without gallstones. This condition is caused when the gallbladder does not contract and therefore does not empty normally in response to a meal. This condition can be diagnosed with a CCK-HIDA scan. This test measures the amount of gallbladder emptying after a radiographic tracer has been given. If the gallbladder ejection fraction is less than a certain percentage (also another area of controversy) then cholecystectomy might be indicated.

So what happens to digestion when the gallbladder is removed?

Gallbladder Removal

Removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) is one of the most frequently performed operations. Typically done with laparoscopic techniques, it’s often indicated for treatment of gallstone-related conditions such as cholecystitis. The question usually asked is “What will this do to my diet or my digestion.”

The usual answer is, “Not much. Maybe nothing.”

There are relatively rare cases of postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS) with persistent pain in the abdomen and digestive distress. A very small percentage of patients may complain of chronic diarrhea after removal of their gallbladder, but this almost always improves if a heart healthy diet is followed. Otherwise, for most people diet and digestion seem normal.

When the gallbladder is gone, the liver bile continues to flow into the upper intestine – only it’s not as concentrated nor is the flow responsive to the amount of fat arriving at the intestine. In theory, this doesn’t make much difference. In practice, it might limit the amount of fat the digestive system can process at one time.

If the gallbladder is dispensable, as many believe, then why is it there? It’s a legitimate question. The suspicion of many researchers is that the contribution of the normal gallbladder to digestion is subtle. That‘s why its removal is not life threatening. In fact, for most people it is not noticeable. This does not mean the digestive system is better or even ‘normal’ without the gallbladder only that it continues to function sufficiently.