What is Hernia?

A hernia is a condition in which a part of an organ pushes through the opening of the organ wall made up of muscle tissue or membranous material. The most common site for hernias to develop is the abdomen. Hernias may or may not display any outward symptoms.

A hernia is a hole in the abdominal wall

Hernias are usually treated surgically. If the blood supply at the herniated portion is cut off then it becomes a medical emergency. Muscle weakness and straining too hard at an activity can cause hernias. Familial factors are probably the most common contributory causes. Smoking and diabetes are lifestyle choices that impair the strength of our natural tissues and can contribute to the formation of hernias as well.

Symptoms of hernia

Symptoms vary with the type of hernia and its underlying cause. The symptoms can manifest suddenly or be present for a length of time. Hernias can often exist as painless bulges. Any convexity in the abdominal region, thigh, chest, and scrotum should be checked for hernia. Hernia bulges are more prominent standing than when in the prone position. Hernia bulges can gradually increase with time. Burning sensation and pressure, especially when muscles in the affected area are strained, are symptoms too.

In the early stages, hernias are often reducible, i.e. they can be pushed back gently into place. However, they can often become irreducible or incarcerated. This means that the bulge cannot be manipulated back into its original position.

Reducible hernias appear as lumps that may hurt but are not tender to touch. Often, the discovery of the lump is preceded by pain. An increase in abdominal pressure, such as when coughing, can momentarily increase the size of the lump.

Irreducible hernias are painful protuberances that are too large to be pushed back. These hernias can often grow without any external signs or discomfort. An irreducible hernia can lead to a strangulated hernia in which the blood supply to the trapped portion is cut off. Pain is typically present when there is entrapped intestine. Bowel obstruction, nausea, and vomiting may also occur.

Causes of hernia

- Congenital weakness of the abdominal wall

- Pregnancy

- Surgery

- Lifting heavy weights

- Chronic constipation

- Chronic cough

- Obesity

- Chronic lung condition

- Fluid in the abdominal cavity

Types of hernia include

Holes in Abdominal Musculature

Femoral hernia – This occurs in the passage between the abdomen and the thigh near the spaces of the femoral vessels. Although a constricted space, sometimes it becomes large enough to allow the intestine to enter and bulge from the upper thigh region just under the groin. This is more common in women then men.

Inguinal hernia– An inguinal hernia is characterized by the protrusion of the contents of the abdominal cavity into the inguinal canal. This is a very common type of hernia, accounting for 75% of all hernias. These are five times more common in men than in women.

Epigastric hernia – These are small hernias, often too small to be detected. They are found between the navel and the breastbone and involve a little bit of fat protruding from weak abdominal muscles.

Umbilical hernia – These are common in newborn babies. The site of the hernia is the abdominal wall under the navel. Even if the weak portion of the abdominal wall closes during infancy, there is a chance that the hernia might recur at a later age.

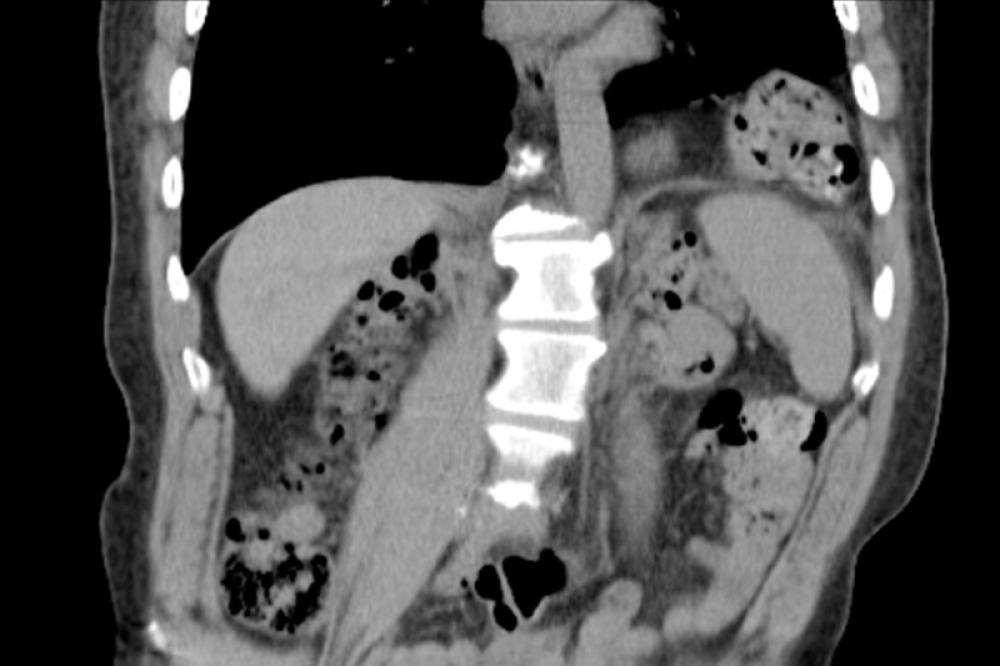

Obturator hernia - This is a rare type of abdominal hernia found mostly in women. It obstructs bowel movement and can cause nausea and vomiting. This hernia is difficult to diagnose because there are no external signs.

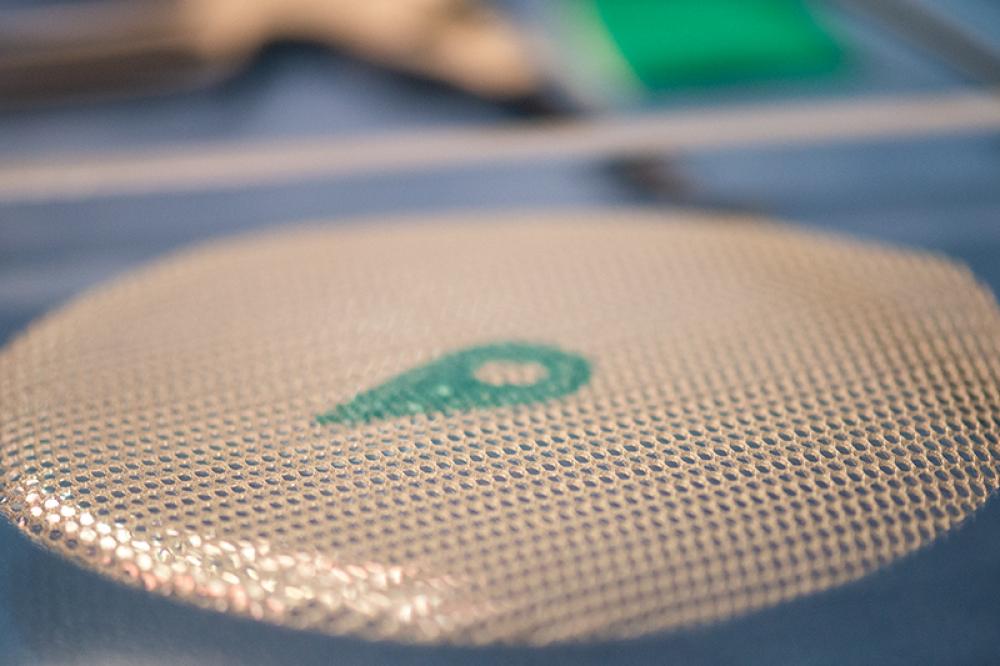

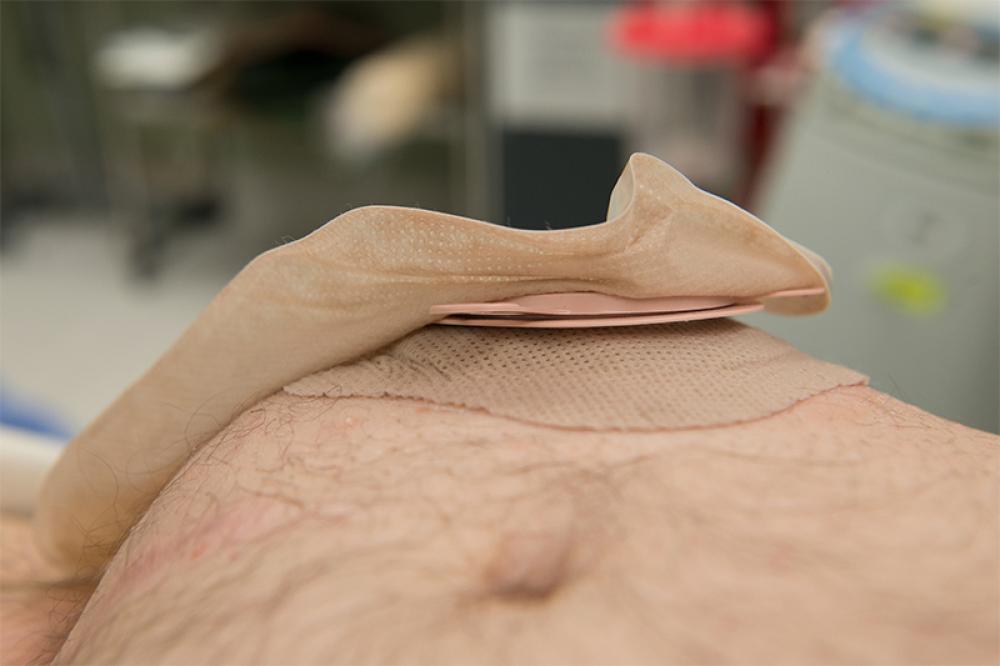

A hernia is a hole that is often patched with Mesh

How are hernias treated?

Hernias are invariably repaired via surgery. Usually, in a surgical procedure after careful sterilization and anesthesia, the margins of the weak area are carefully defined. The hole is then sutured and a synthetic mesh may also be added. Suturing requires skill otherwise the strain on the edges of the defect can cause another hernia over time. Over time different styles of suturing have been devised such that deep tissue layers are sutured in order to minimize stress on the edges of the weak muscle. If the muscle is too weak to take the strain of suturing, plastic wires mesh or screen may be used to cover the hole.

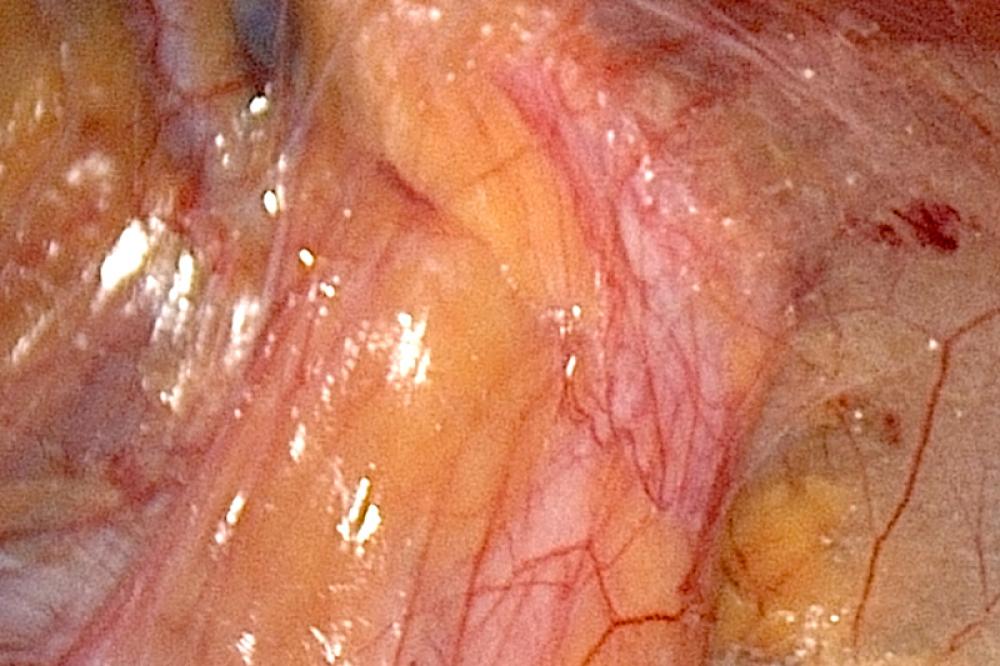

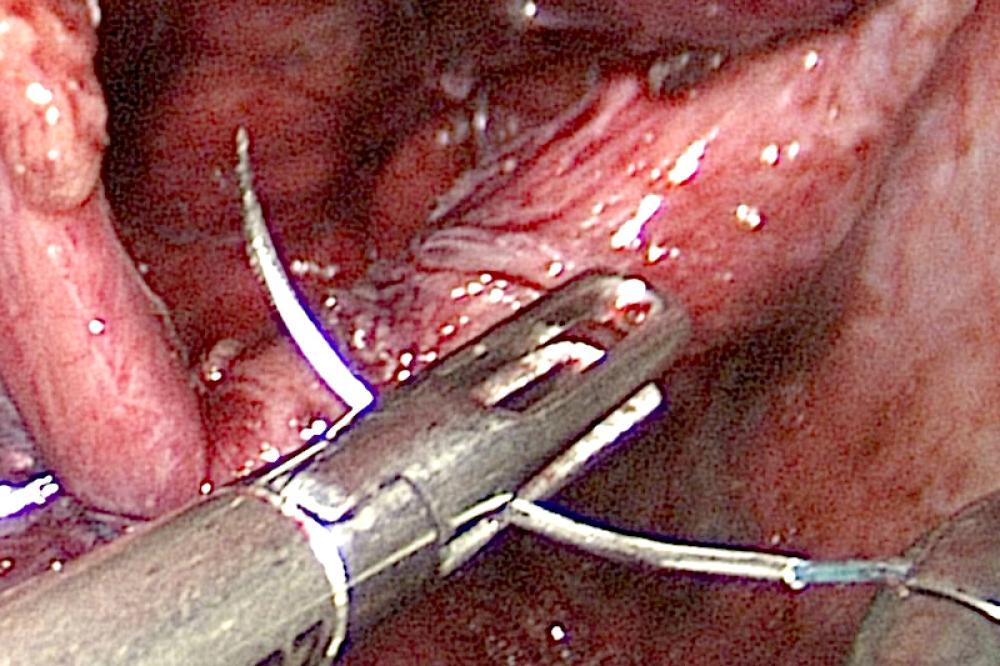

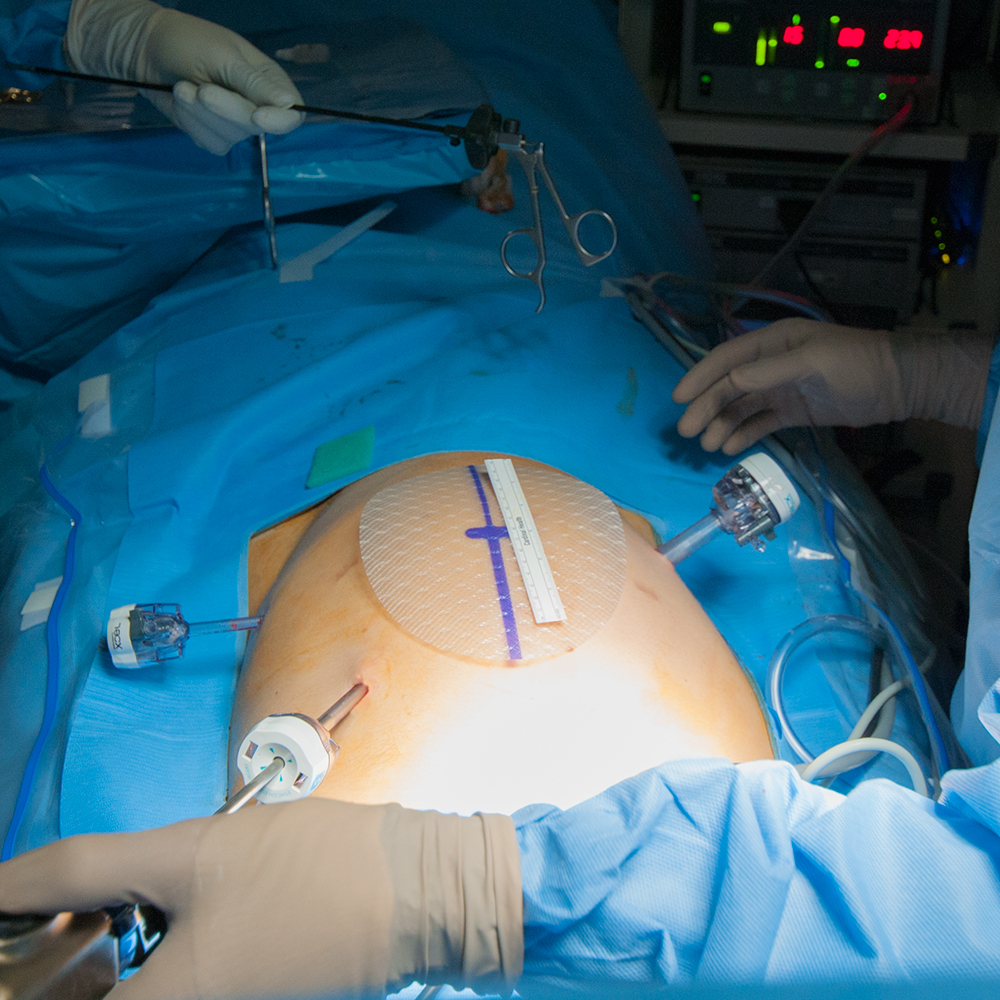

Laparoscopy has emerged as a favored technique for treating hernia, particularly in cases where hernias have recurred at the same site. The main advantage with laparoscopic surgery is that the incisions made are relatively small; this enables the surgeons to minimize injury to the abdominal area. The method is particularly effective in treating hernias in the groin area. Post-operative pain is reduced and there is less chance of the hernia recurring. Hernia repairs for adults are usually carried out under general anesthesia; the surgeon can also opt for local anesthesia and sedatives if he feels these are better suited to the patient’s general health.

Large Mesh Placed Through a Small Opening

After the surgery

There are many possible complications after hernia surgery that depend on the location of the hernia and the contents of the hernia prior to its repair. Damage to the intestines is always possible during abdominal surgery. Possible complications after inguinal hernia surgery, for example, include urinary retention, infection, and persistent fluid collections. After the surgery, it is suggested that you maintain a routine that incorporates walks and light stretching exercise. Eat fiber-rich foods, vegetables, and stay hydrated so that you do not have to strain when moving bowels. Avoid smoking as it can lead to persistent cough which can exacerbate a hernia. Keep away from strenuous exercise so that your body has time to heal.

Simple hernia repairs can be performed on an outpatient basis. For complicated cases, a few days in the hospital may be required. It is advisable to eschew lifting weights for 4-6 weeks after a hernia surgery.

The prognosis with hernias is generally good subject to timely diagnosis and treatment. Minimizing the risk factors after surgery is important. Old age, size of hernia, duration of irreducibility are other factors that can impact prognosis.

Preventing hernias

Hernias cannot really be prevented; the risk of developing hernia depends upon factors such as the arrangement and thickness of local tissue. These attributes are inherited. On our part, we can ensure muscle health by regular exercise, maintaining an optimum bodyweight, and using correct form when lifting weights. Avoid constipation and incorporate fiber in the diet. Do not smoke and do your best to maintain a healthy weight.